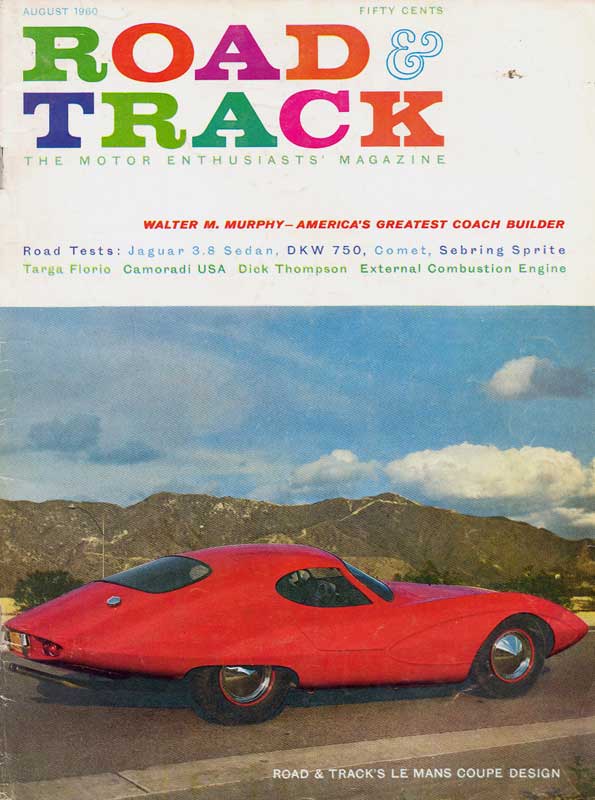

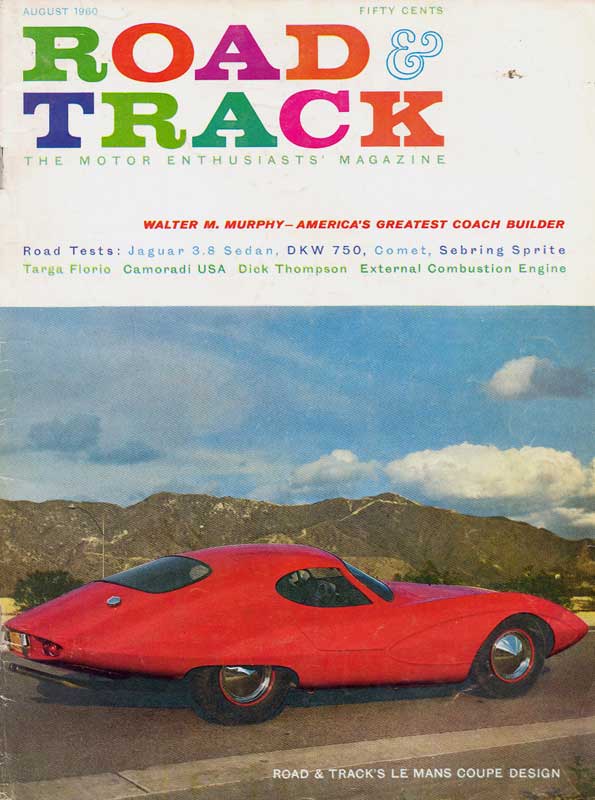

Road & Track magazine, August, 1960. It is interesting to me how a styling exercise can turn into a major project with so little to really go on as to the odds of success, either as a competition car or a design that could be successful in the marketplace. There were so many unknowns and uncertainties. But that is the charm of that era, that people were caught up in their dream and willing to invest their money, time, and talent. Those days are long gone.

Illustration from Stother MacMinn’s book, Sports Cars of the Future.

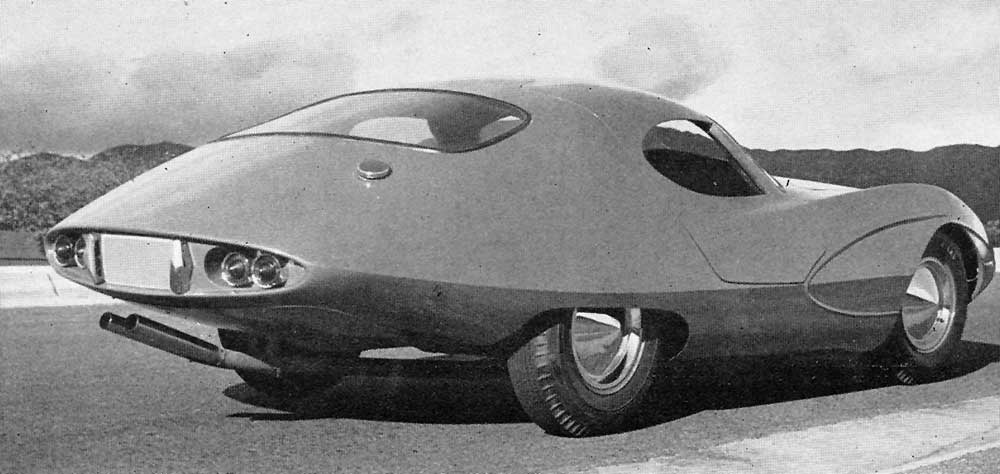

When John Bond, publisher of Road & Track. began to visualize an ideal American car to compete at Le Mans, he based his hypothesis on the idea that possibly someone of limited means but immense ambition would build it. Under the title of Sports Car Design and as No. 39 in that series, the description commenced in November 1957, and ran through the January, February, and April issues of 1958, with a complete analysis of structure, detail, accommodation, and body form, all carefully coordinated toward creating a serious contender for the famed 24-hour race. Chassis components were all derived from available manufactured items, with the exception of the frame itself, and this custom-fabricated item was kept as simple and inexpensive as possible, being merely two parallel box-section rails.

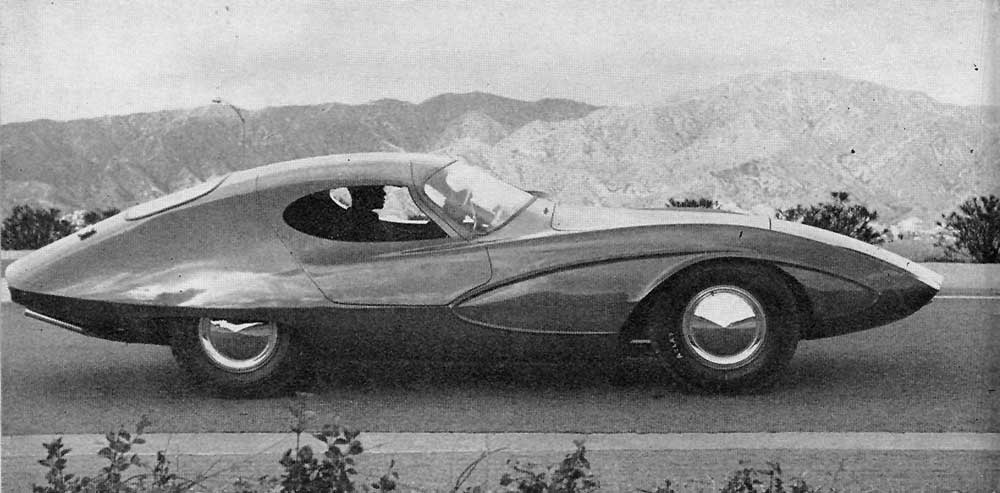

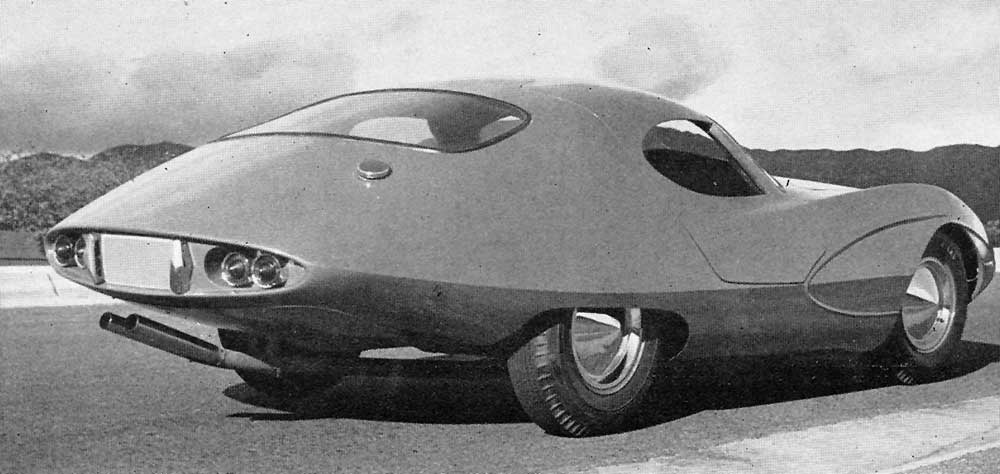

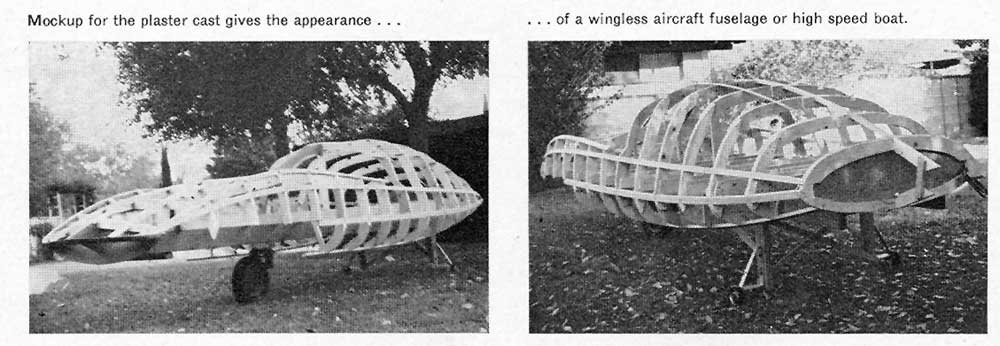

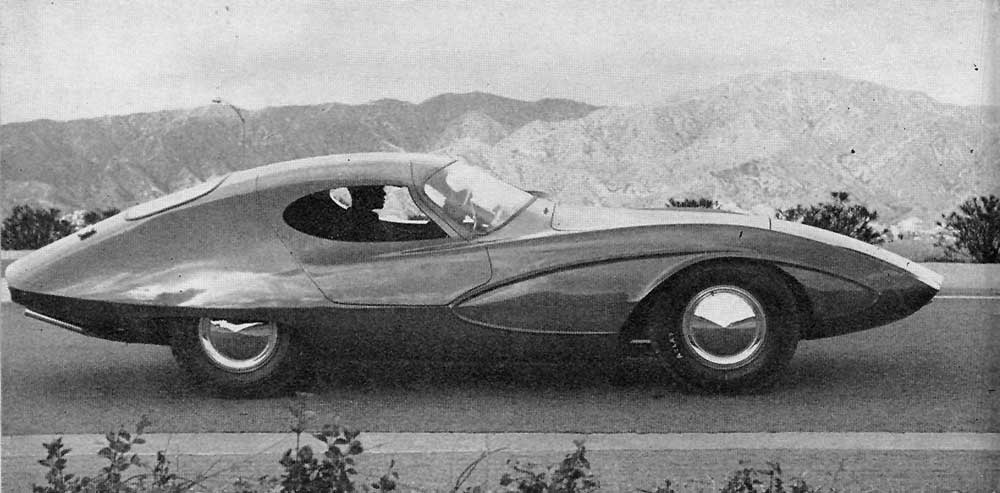

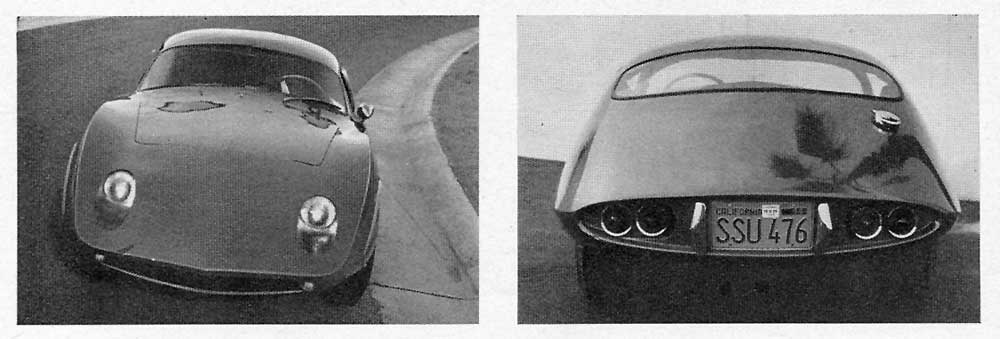

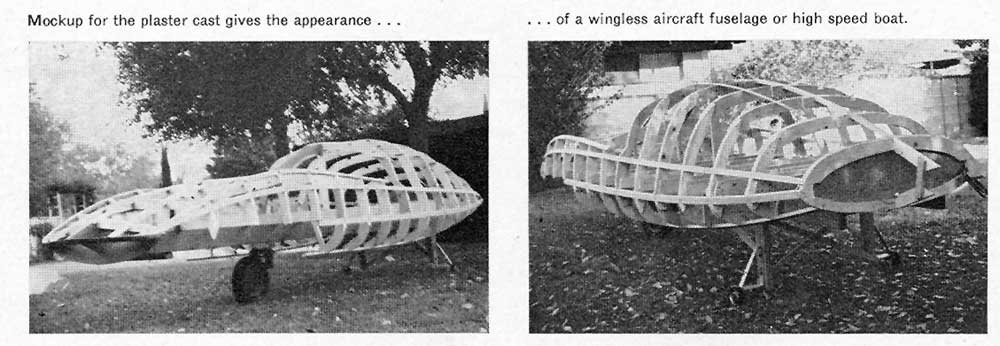

A number of people wrote, expressing definite interest in attempting the project, and the series of articles actually did trigger three dedicated Southern California enthusiasts into action. Marvin Hortan, an electronics technician for a ram-jet manufacturing corporation, father of three, and a solidly qualified amateur sports car engineer, had long had dreams of an ideal sports competition car that was far from anything offered by current manufacturers. Although his chassis concept differed somewhat from Bond’s, he felt that the general body envelope suited his purpose very well, an opinion shared by friend and electronics co-worker Ed Monegan, whose long experience in high-speed boat building was to provide invaluable. Using the published body drawings as a rough basis, they completed a full-size lines loft in June of 1958 and began a wood frame for the male body plug, which was three-quarters complete in August, when they contacted the author. A clay model that had been used as a basis for the design was transferred to Horton’s Pacoima home where the work was being done. In consideration of the high-speed runs to be attempted with the car, Hortan decided to raise progressively the rear of the body, beginning amidships, in order to cancel more of the top surface negative pressure behind the cab, and add more in the underpan area. This change, accomplished in the wood frame stage, resulted in an upswept “platform line” crease on the body’s side, but provided a more efficient tail conformation.

Clay, as a mold plug medium, was prohibitively expensive, so plaster was used to fill in the frame. It took several months to refine the surfaces and general shape with a grinder, primer, putty, and endless hours of patient work.

About February of 1959, Alton Johnson, another enthusiast with real and individual ambitions and extensive fiberglass experience with the Victress Manufacturing Company, had nearly completed a chassis of his own, with dimensions coincidentally close to the original Bond idea. He contacted Horton, and it was agreed that for his help in finishing the body plug and mold he would receive the first shell.

The mold was completed by June of 1959, and a superlight basic body form, sans windows and rear wheel cutouts, was cast and transferred to Johnson’s operation area at Victress.

Horton then returned to his own chassis fabrication, which was completed and running by February of 1960, having been delayed by an Olds engine installation in a Studebaker and a compete one-off Formula Junior project. On the coupe, he elected to use wishbones and longitudinal torsion bars (machined from pre-1949 Ford driveshafts) for the front suspension, but a transverse leaf spring (as suggested in the article) provided weight support for the independent rear. A space-tube frame, tied in with a structural aluminum reinforced fiberglass driveshaft shaft tunnel provided the lowest possible seating between side members, and a firm body mounting. His program is due for completion about mid-summer of this year.

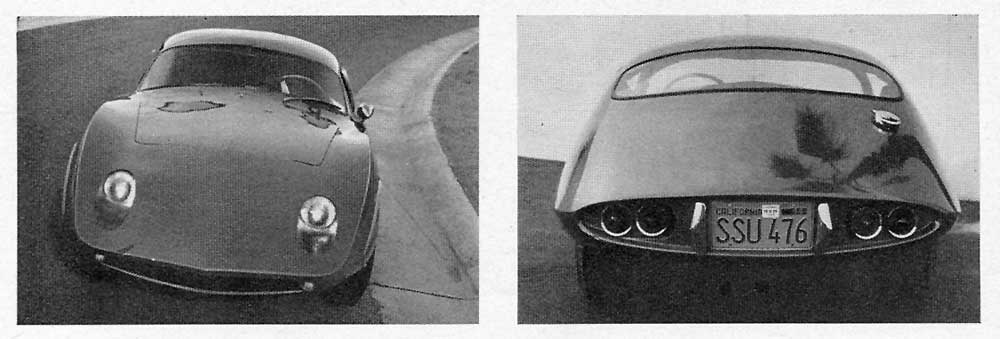

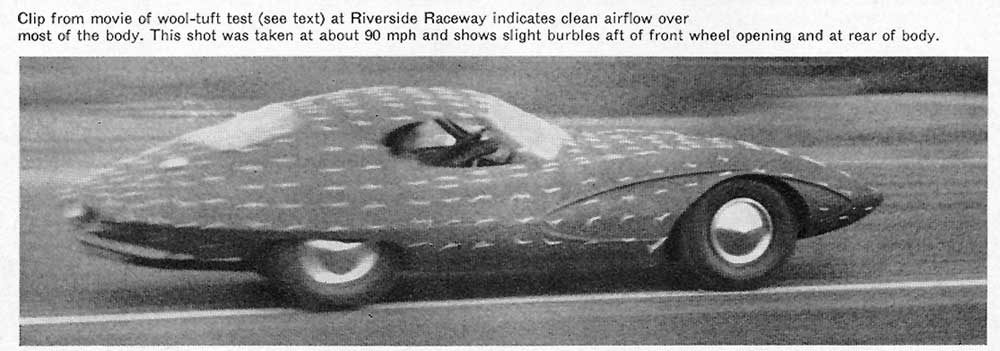

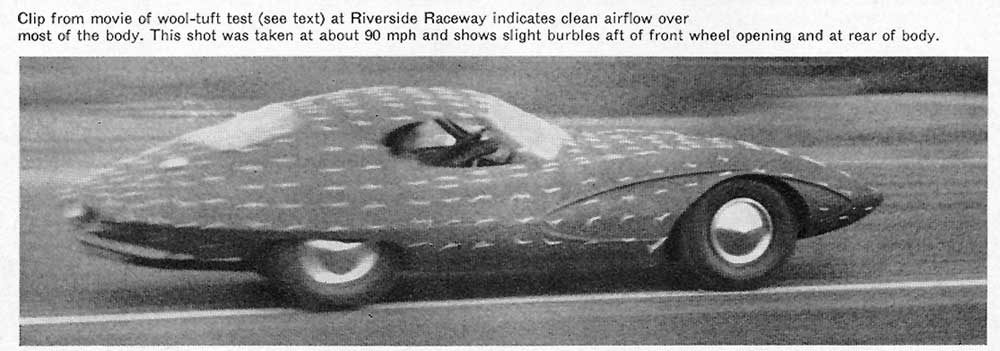

johnson had his own chassis enclosed in the first body by August of 1959, when it was possible to run an airflow observation test at the Riverside International Raceway. White wool tufts for determining air-flow direction were easily visible against the dark grey primer, and sections that had already been cut out of the body for the two headlight tunnel openings were carefully taped back into place to provide a completely smooth form. Howard Miereanu (now a General Motors designer, but then a student at the Art Center School in Los Angeles), possessor of a Bolex 16-mm motion picture camera, was perched in the passenger seat of an accompanying car and panned past the coupe which was run at steady speeds of 60, 70, 80, 90, and 100 mph down the 5,100-ft back straight of the race course. Viewing this film at slow speed later confirmed theories that some of the top boundary layer could be diverted around the corners of the cab by use of a sharply peaked cowl and windshield, and that the general air flow was true to the developed contours with a minimum of turbulence.

One of the world’s greatest automotive aerodynamicists, upon analyzing a still picture of this test, expressed concern over the sharp edges of the fender sections as a barrier to smooth cross-flow, and the obvious desirability of a complete undertray (which Johnson’s car did not have), but satisfaction with the flow behavior around the cab.

Johnson has since built an entirely new chassis for his car, using the original Chevrolet engine, but an all-independent wishbone suspension with coil springs, and disc brakes, all of which should be covered by a revised version of the original body by mid-summer.

Since Horton’s “original” car will probably be licensed about the same time, or possibly earlier, it should make this dual culmination of Bond’s far-reaching suggestion a most exciting reality.

Sports Car Design Realized

Road & Track’s Le Mans Sports Car Design, as built by a small group of enthusiasts

By Strother MacMinn

This article was first publish

Photos of the LeMans Coupe from Hot Rod Magazine, June, 1960, and photos of an unrestored surviving car owned by Geoffery Hacker.

Illustration from Stother MacMinn’s book, Sports Cars of the Future.

When John Bond, publisher of Road & Track. began to visualize an ideal American car to compete at Le Mans, he based his hypothesis on the idea that possibly someone of limited means but immense ambition would build it. Under the title of Sports Car Design and as No. 39 in that series, the description commenced in November 1957, and ran through the January, February, and April issues of 1958, with a complete analysis of structure, detail, accommodation, and body form, all carefully coordinated toward creating a serious contender for the famed 24-hour race. Chassis components were all derived from available manufactured items, with the exception of the frame itself, and this custom-fabricated item was kept as simple and inexpensive as possible, being merely two parallel box-section rails.

A number of people wrote, expressing definite interest in attempting the project, and the series of articles actually did trigger three dedicated Southern California enthusiasts into action. Marvin Hortan, an electronics technician for a ram-jet manufacturing corporation, father of three, and a solidly qualified amateur sports car engineer, had long had dreams of an ideal sports competition car that was far from anything offered by current manufacturers. Although his chassis concept differed somewhat from Bond’s, he felt that the general body envelope suited his purpose very well, an opinion shared by friend and electronics co-worker Ed Monegan, whose long experience in high-speed boat building was to provide invaluable. Using the published body drawings as a rough basis, they completed a full-size lines loft in June of 1958 and began a wood frame for the male body plug, which was three-quarters complete in August, when they contacted the author. A clay model that had been used as a basis for the design was transferred to Horton’s Pacoima home where the work was being done. In consideration of the high-speed runs to be attempted with the car, Hortan decided to raise progressively the rear of the body, beginning amidships, in order to cancel more of the top surface negative pressure behind the cab, and add more in the underpan area. This change, accomplished in the wood frame stage, resulted in an upswept “platform line” crease on the body’s side, but provided a more efficient tail conformation.

Clay, as a mold plug medium, was prohibitively expensive, so plaster was used to fill in the frame. It took several months to refine the surfaces and general shape with a grinder, primer, putty, and endless hours of patient work.

About February of 1959, Alton Johnson, another enthusiast with real and individual ambitions and extensive fiberglass experience with the Victress Manufacturing Company, had nearly completed a chassis of his own, with dimensions coincidentally close to the original Bond idea. He contacted Horton, and it was agreed that for his help in finishing the body plug and mold he would receive the first shell.

The mold was completed by June of 1959, and a superlight basic body form, sans windows and rear wheel cutouts, was cast and transferred to Johnson’s operation area at Victress.

Horton then returned to his own chassis fabrication, which was completed and running by February of 1960, having been delayed by an Olds engine installation in a Studebaker and a compete one-off Formula Junior project. On the coupe, he elected to use wishbones and longitudinal torsion bars (machined from pre-1949 Ford driveshafts) for the front suspension, but a transverse leaf spring (as suggested in the article) provided weight support for the independent rear. A space-tube frame, tied in with a structural aluminum reinforced fiberglass driveshaft shaft tunnel provided the lowest possible seating between side members, and a firm body mounting. His program is due for completion about mid-summer of this year.

johnson had his own chassis enclosed in the first body by August of 1959, when it was possible to run an airflow observation test at the Riverside International Raceway. White wool tufts for determining air-flow direction were easily visible against the dark grey primer, and sections that had already been cut out of the body for the two headlight tunnel openings were carefully taped back into place to provide a completely smooth form. Howard Miereanu (now a General Motors designer, but then a student at the Art Center School in Los Angeles), possessor of a Bolex 16-mm motion picture camera, was perched in the passenger seat of an accompanying car and panned past the coupe which was run at steady speeds of 60, 70, 80, 90, and 100 mph down the 5,100-ft back straight of the race course. Viewing this film at slow speed later confirmed theories that some of the top boundary layer could be diverted around the corners of the cab by use of a sharply peaked cowl and windshield, and that the general air flow was true to the developed contours with a minimum of turbulence.

One of the world’s greatest automotive aerodynamicists, upon analyzing a still picture of this test, expressed concern over the sharp edges of the fender sections as a barrier to smooth cross-flow, and the obvious desirability of a complete undertray (which Johnson’s car did not have), but satisfaction with the flow behavior around the cab.

Johnson has since built an entirely new chassis for his car, using the original Chevrolet engine, but an all-independent wishbone suspension with coil springs, and disc brakes, all of which should be covered by a revised version of the original body by mid-summer.

Since Horton’s “original” car will probably be licensed about the same time, or possibly earlier, it should make this dual culmination of Bond’s far-reaching suggestion a most exciting reality.

Sports Car Design Realized

Road & Track’s Le Mans Sports Car Design, as built by a small group of enthusiasts

By Strother MacMinn

This article was first publish

Photos of the LeMans Coupe from Hot Rod Magazine, June, 1960, and photos of an unrestored surviving car owned by Geoffery Hacker.

- Related articles

- Mercedes-Benz Classic: New in its full splendour - The oldest SL (hydro-carbons.blogspot.com)

- Armstrong Siddeley (hydro-carbons.blogspot.com)

- Spyker Lands in America With 400+ HP Impact! (hydro-carbons.blogspot.com)

- Microcar collection at Whiteman Park (hydro-carbons.blogspot.com)

- Lazareth's 250 hp, Ferrari-powered Wazuma V8 quad for sale (hydro-carbons.blogspot.com)

- Ferrari V4-Motorcycle Concept (hydro-carbons.blogspot.com)

- macminn's-lemans-coupe (hydro-carbons.blogspot.com)

No comments:

Post a Comment