The Museum contains several other IC engines with

rotary valves, but this is not their main unusual feature.

See them on their respective pages:

INTRODUCTION

For almost all its history, the preferred valve for the Internal Combustion engine has been the poppet type. (the etymology of the word "poppet" is an interesting study in itself, but a bit off-topic) There are good reasons for this; see the Appendix on the advantages of the poppet valve.

However, many inventors have been attracted by the apparent simplicity and the uniform motion of rotary valves of one kind or another. There is also the tempting prospect of being able to run on inferior fuels because there was no hot exhaust valve always present in the cylinder to trigger pre-ignition. However, as with both steam and IC rotary engines, the simplicity was more apparent than real, and the engineering problems were daunting.

The basic problem, is that the pressures in the cylinder of an internal combustion engine are high, due to both the compression stroke and the explosion of the fuel-air mixture. This produces large forces on the valve system, however it is contrived; the beauty of the poppet valve is that such forces simply push it harder against its seat, and have no effect at all on the valve-actuating mechanism.

However, the geometry of rotary valve systems is inherently different; in the Aspin concept below, the vertical valve cone is pushed up axially against the cylinder head, while the horizontal Cross valve is pressed up against the top half of the bearing surfaces. In both cases this can cause excessive friction and seizure, the root of the problem being that enormous forces are acting on the valve while it is moving.

There were a large number of rotary valve schemes tried, many of which are only known as patents, the practical success or otherwise being lost to history. The first US patents tracked down so far are by Frayer & Howard in 1907 and 1908. Another early patent was in 1911 by Vallillee (Patent 983328) who used a rotating disc. Several other versions by other people were patented later; see the patent list below. In Britain the two systems which gained the most attention were the Aspin vertical rotating valve and the Cross horizontal rotating valve.

Rotary valves were also tried in steam engines, without conspicuous success. See The Paget Locomotive and the Carel engine on the High-Speed Steam Engines page.

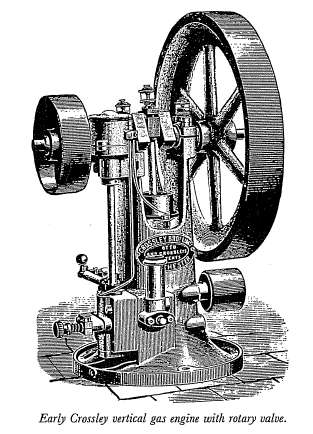

THE CROSSLEY ROTARY VALVE GAS ENGINE: 1886 - 1902

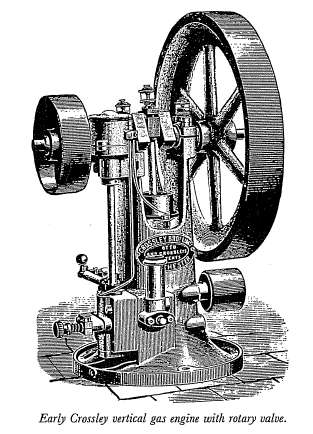

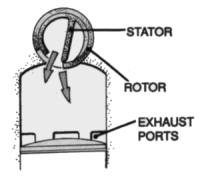

Left: Crossley gas engine with rotary valve.

This is the earliest use of a rotary valve in an internal combustion engine so far discovered. The valve assembly is at the bottom left of the picture, with an adjusting screw sticking out of it. It is driven from the crankshaft by a vertical shaft on the left side of the engine.

Messrs Crossley Bros Ltd (they knew how to name companies in those days) of Openshaw, Manchester, used rotary valves on both vertical and horizontal gas engines running on the Otto cycle. Tube ignition was fitted. Crossley were a successful and respected company, and carried on using these valves from 1886 to 1902; a period of sixteen years that ought to indicate that they worked reasonably effectively and reliably. This is interesting, bearing in mind the problems that later workers struggled with.

The answer is probably that these engines had a very low specific output compared with later designs, and the working pressures were correspondingly low. Also, as a stationary engine, it could be given as much care and adjustment as it needed. In those days it was considered quite normal to give an engine an amount of attention which would be out of the question for, say, a car engine. It was still thought a much better option than a steam engine, where boiler pressure and water level required constant skilled supervision if catastrophe was to be avoided.

Source: Rotary Valve Engines by Marcus Hunter, Hutchinsons 1946

The tireless researchers of The Museum have obtained this unique personal account of a Crossley rotary valve engine in use in 1903:

"Although the engine was several years old, it would toil away hour after hour with an occasional application of ordinary cylinder oil to the rotor, oil probably of an inferior grade by modern standards. There is no doubt that the rotary feature was in many ways a most reliable device; that is to say, there was never a mechanical failure of any kind. On a few occasions the rotor would show signs of overheating, and in these circumstances all that was necessary to regain normal running was to remove the keep from the rotary member, clean the working surfaces with paraffin, and start up again with a fresh application of clean oil.

The keep is spring loaded and adjustable. The operation of adjusting the spring had to be most carefully carried out. The exact loading needed to be such that at maximum engine load, and when thoroughly warmed up, the valve was just on the point of spitting at each explosion. If the spring load was too light, the oil would be blown out each time the engine fired, and if too heavy, any extra expansion of the rotor due to increase in temperature resulted in so much additional friction that the ill-effects became cumulative and the engine would begin to lose speed. However, in spite of all this, the Crossley product was a practical engineering job, and there are many modern appliances which give far more trouble."

Testimony by Marcus Hunter, in 1946. This account refers to the vertical engine illustrated above; it was used for driving machine tools in a private workshop.

The account above is highly revealing. It shows that the Crossley rotary valve engine required almost constant attention, ongoing and critical adjustment of the valve loading, and periodic dismantling.

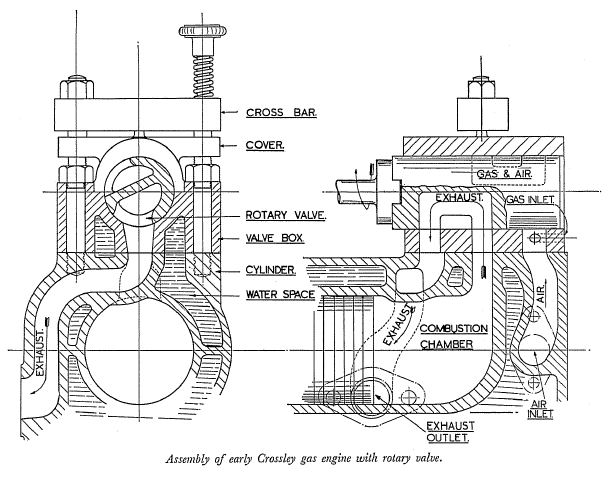

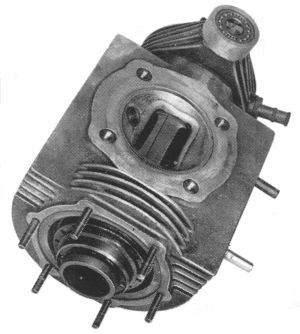

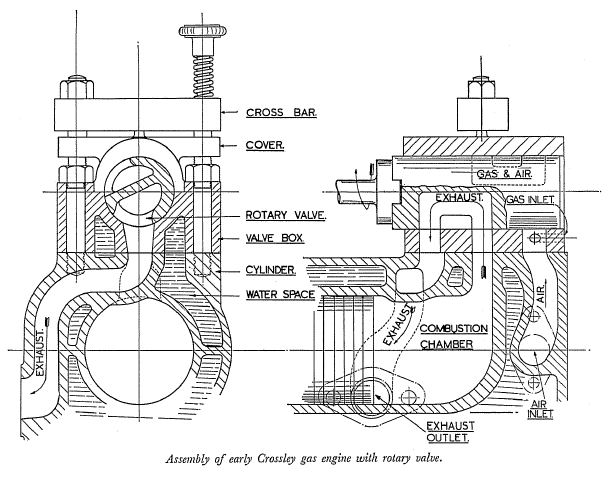

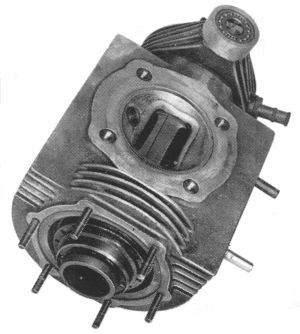

Left: Inside the Crossley rotary valve.

In this version the cylinder bore was 4.5 inches, and the valve bore 3 inches. The cross bar and cover allowed an adjustable pressure to be put on the valve by springs, to maintain sealing. The valve and the valve box were made of ordinary cast iron as generally used for engine cylinders, and indeed all sorts of machinery, at that date.

Note the convoluted gas passages. In particular, the exhaust passage turns back and runs right past the cylinder wall, which does not look as if it would help cooling.

Source: Rotary Valve Engines by Marcus Hunter, Hutchinsons 1946

Since 1988 Crossley has been part of the Rolls-Royce Power Engineering group.

THE FRAYER & HOWARD ROTARY VALVE PATENT: 1907

Left: Frayer & Howard rotary valve patent: 1907

This is the earliest internal-combustion rotary valve patent so far unearthed by the untiring staff of The Museum. Note however that Butler was apparently using rotary valves in a compound IC engine in 1904.

The valve is mounted horizontally across the top of the cylinder, like the Cross valve, and driven continuously by chain and sprocket from the crankshaft at half-speed.

Frayer and Howard do seem to have had some idea of what they were up against. The valve, shown in Figs 3 and 4, was designed not to touch the surounding metal, but maintain a 2-thou clearance, the gap being flooded with lubricating oil. The valve rotated in ball bearings at each end, protected from the exhaust gases by two sets of sealing rings. (19,20,21,22) It sounds plausible, but I wonder how much oil would be lost into the induction and exhaust passages.

Nothing is currently known as to how much success Frayer and Howard had with their invention. They are unknown to Google.

US Patent 908,656

THE VALLILLEE ROTARY VALVE PATENT: 1911

Left: The Vallillee rotary valve patent: 1911

The rotary valve has an H cross-section and sits on top of the cylinder. It is rotated intermittently via cam 38 and lever 35, that work a ratchet drive 42 on top of the cylinder, the idea presumably being that the valve would be stationary during the parts of the combustion cycle that had high-pressure in the cylinder and would tend to jam the valve.

This is the first known proposal to use intermittent drive to a rotary valve. It looks rather impractical to me.

Leonard Archibal Vallillee lived in Buckingham, in the province of Quebec. Unlike most of the inventors in these pages, he is known to Google. He was born in 1887, the son of John Edward Vallillee (born circa 1863 in Buckingham, Quebec) and Mary McCormick.

US Patent 983,328

ROTARY VALVES BECOME THE VOGUE

In the period 1911-1912 there was a remarkable flurry of activity in the field of rotary valves. Engines using them were unveiled by Itala, Castiglione-Bolton, and Darracq in Europe, and by Mead, Reynolds and The Silent Valve Company in the USA. Rotary valves had, to some extent, become the fashion. But they still did not work very well.

THE ITALA ROTARY VALVE: 1911

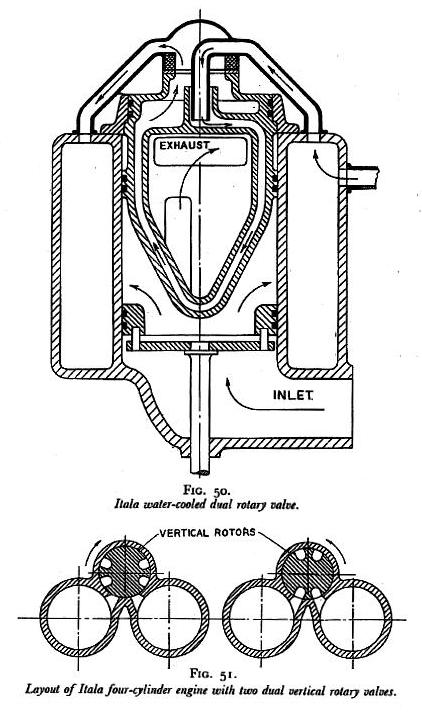

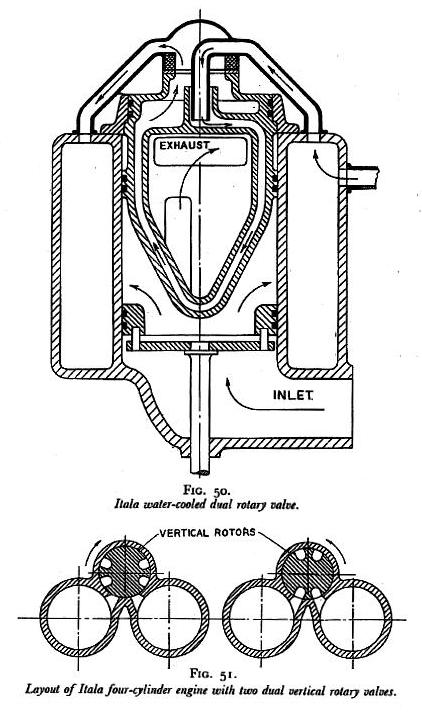

Itala was a car manufacturer based in Turin, Italy from 1904-1935. See Itala in Wikipedia. Water-cooled rotary valves were fitted to models announced at the 1911 Olympia Motor Car Show. At first only a 35 HP model was displayed, but 25 and 50 HP versions were said to be on the way.

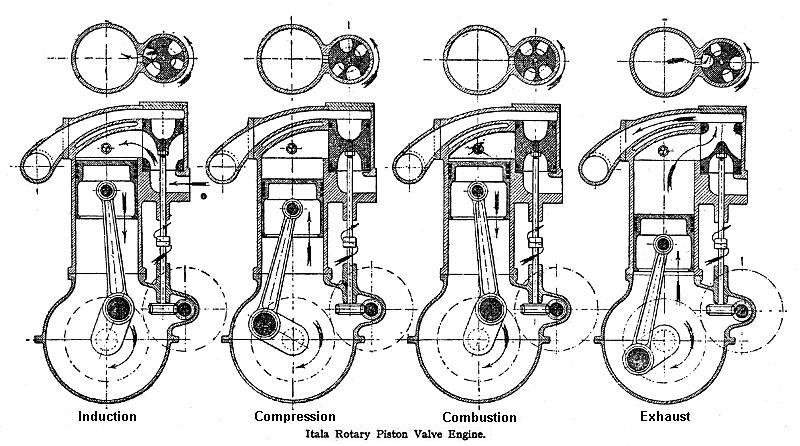

Left: The Itala rotary valve : 1911

Two rotary valves were used, each placed vertically and serving the two adjacent cylinders. Each cylinder had only one port, which carried both inlet and exhaust, while the valve, which turned at one-quarter engine speed, had an internal division so that the inlet was drawn in from the bottom and the exhaust passed out through the top.

Cooling water for the valve passed into it at the centre, passed down one side of the valve body and up the other, and left by an annular port at the top. A centrifugal pump assisted water circulation.

The crankshaft carried a helical gear that drove a side shaft; this in turn drove the two vertical valve spindles through 'high-efficiency' worm gears. Each valve spindle incorporated a breaking-piece (presumably some sort of shear-pin) to minimise damage to the engine if one of the valves seized.

A small hole was drilled through the valve body in such a position that it carried the pressure on firing through to the opposite side of the valve, into a recess of the same area as the valve port, to balance the loading.

Despite ingenious design, high standards of construction, and some very favourable reports (eg from Autocar) the Itala valve did not prosper. Hunter says "...it is evident from a careful study of the design that it calls for the highest grade of materials and workmanship; in fact every technical defect which might be possible seems to have been overcome by lavish expenditure and detail embellishment... these opinions are expressed: (1) there are too many parts, and (2) skilled experience is required for maintenance, greater than can generally be commanded..."

This is all a bit vague; perhaps however it boils down to the Itala rotary valve being expensive and unreliable. I suspect those "breaking-pieces" saw a lot of action.

Source: Rotary Valve Engines by Marcus Hunter, Hutchinsons 1946

Rankin Kennedy's "The Book of the Motor Car" published in 1913, had this to say:

"Now for the first time a high-speed multiple cylinder engine without reciprocating parts, is available in a throughly practical form, so well thought out in detail and so beautifully constructed that its possession and use cannot be less satisfactory to the fortunate owner than the contemplation of the design is to the engineering critic." which, quite frankly, is laying it on a bit thick. One can only assume that news of valve troubles had not reached Mr Kennedy before publication.

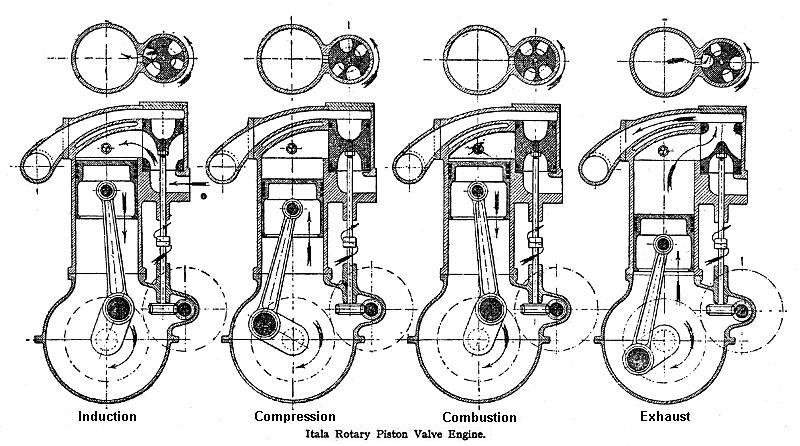

Left: Operating cycle of the Itala rotary valve: 1912

Starting with induction and ending with the exhaust stroke. Note the Oldham coupling in valve shaft. This incorporated the 'breaking piece'.

From The Book of the Motor Car Rankin Kennedy, published Caxton 1913

From 1924 the Itala company was being run in receivership. It was bought by truck maker Officine Metallurgiche di Tortona in 1929, and a few more cars were produced, ending in 1935. After that, what was left of the Itala company was bought by Fiat.

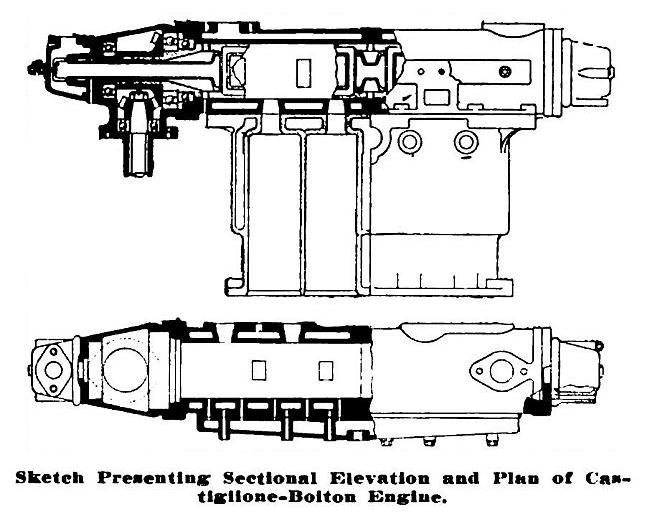

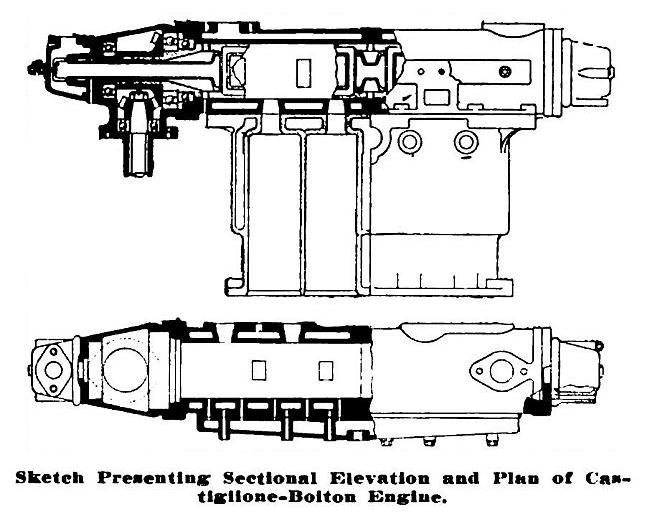

THE CASTIGLIONE-BOLTON ROTARY VALVE: 1912

This British rotary valve scheme was put foreward by Castiglione and Bolton. The valve was horizontal, running the length of the engine

Left: Castiglione-Bolton rotary valve engine: 1912

The rotary valve was driven by a vertical shaft through bevel-gearing. It had a water-cooling jacket on its outside, accessed at each end by pumped cooling water.

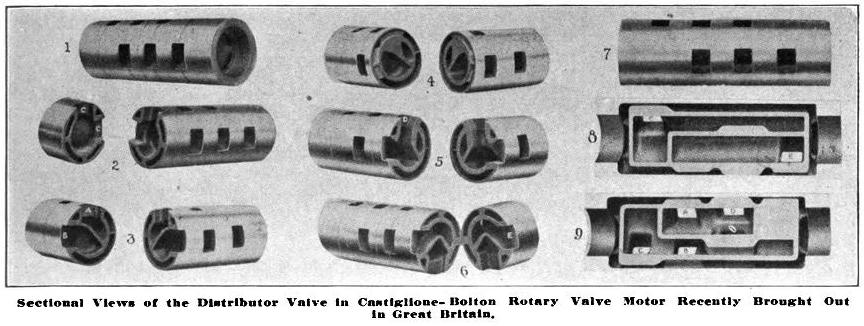

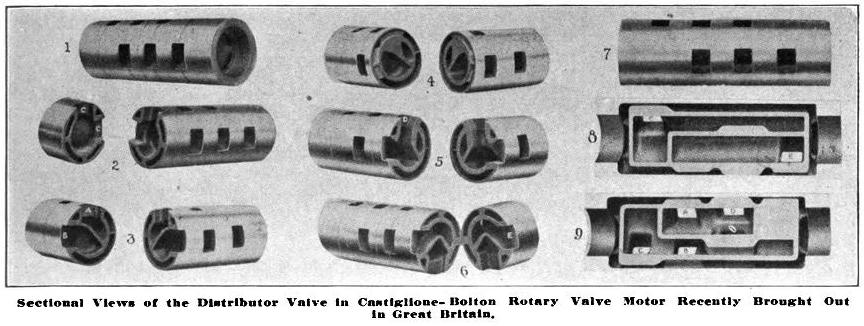

Below: The Castiglione-Bolton rotary valve: 1912

The valve had a complex system of inlet and exhaust porting, which connected to the cylinder via a single port in the top of the roughly hemispherical combustion chamber.

The view at 7 is of a complete valve for two cylinders.

From the The Automobile Journal Volume 33. Number 7 May 10, 1912, page 46

The engine seems to have had little success, as the Castiglione-Bolton team is unknown to Google. It also seems to have escaped the notice of Hunter.

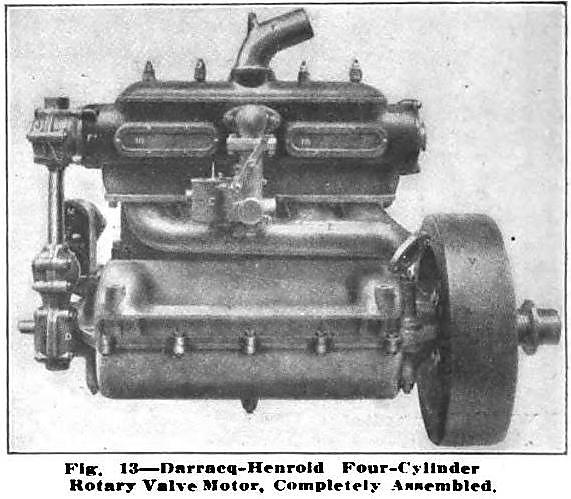

THE DARRACQ-HENRIOD ROTARY VALVE: 1912

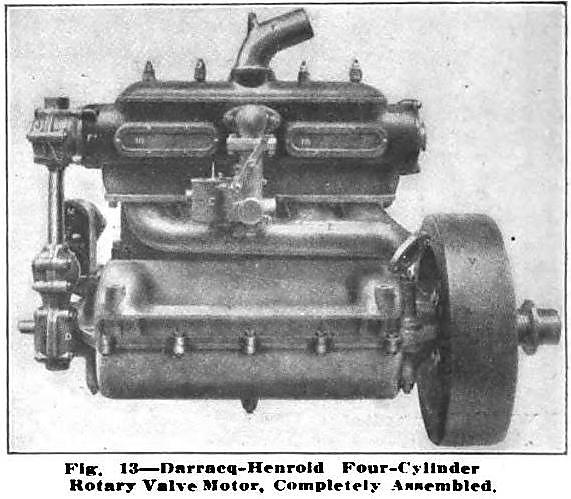

The Darracq-Henrold rotary valve engine was a French design, from the well-known car firm of Darracq. According to one source "In 1912 the firm succumbed to the vogue for abolition of the poppet valve with a near disastrous range of rotary valved cars under Henriod patents." which sounds as if things didn't go too well, and also gives a hint as to why so many rotary valves appeared around 1912- it was "the vogue".

In 1912 Darracq produced "syst�me Henriod" engines of 2613 cc and 15 HP (uprated to 2951 cc the next year) and a 3969cc version of 20 HP.They were described as Type SS, or 'sans soupapes', meaning without valves- not strictly true, of course. Hunter says, apparently acidly, "'Sans soupapes' is the term which the French give to every engine which has other than poppet-valves." These engines were also described as "completely gutless", presumably due to breathing difficulties, and were prone to seizure. Both profits and Darracq's reputation plummeted, and the debacle seems to have prompted Alexandre Darracq to retire from car manufacture; he sold his company to British financial interests in 1913. Apparently one 1912 SS car is still in existence, but in need of restoration. According to Hunter (p102) only a few engines actually reached customers, so for the effect on the company to be so drastic, their performance must have been truly awful.

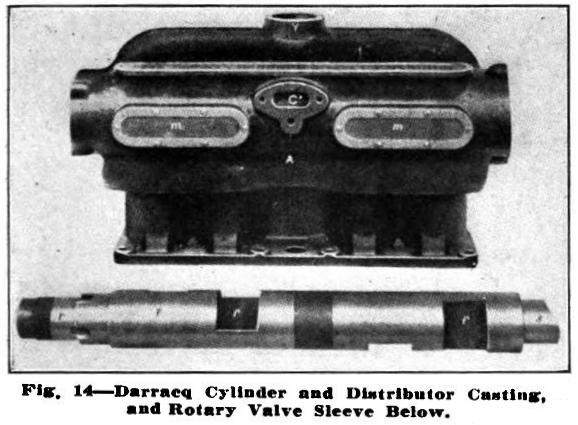

Left: A Darracq four-cylinder engine with rotary valve: 1912

The horizontal valve ran the length of the cylinder block, being driven from the crankshaft at half engine speed by a vertical shaft with skew gears. The ignition magneto can be seen to the left behind the vertical shaft.

Look at the size of that flywheel!

From The Automobile Journal Volume 33, Number 6, 25 April 1912; p18,19. The article spells Henriod as Henrold throughout.

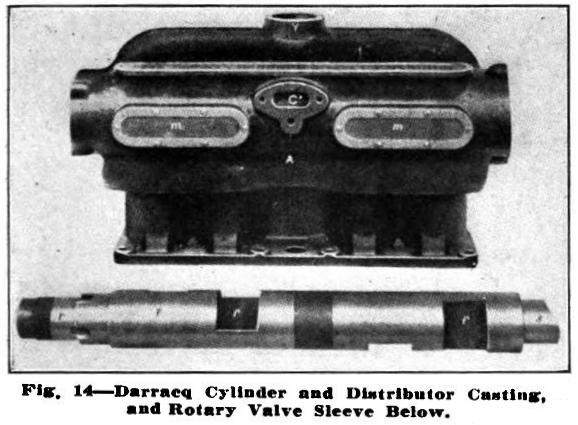

Left: The Darracq rotary valve: 1912

Pretty much self explanatory.

THe flange marked C is for mounting the carburettor. The covers m presumably allowed inspection of the valve.

From The Automobile Journal Volume 33, Number 6, 25 April 1912; p18,19.

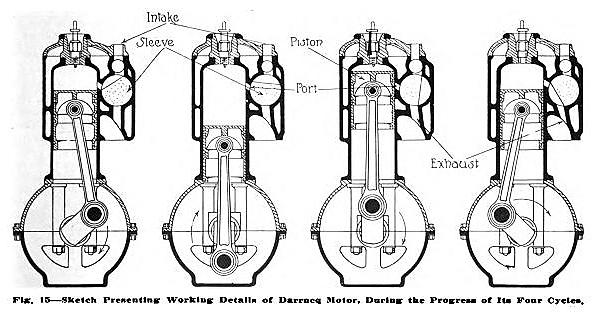

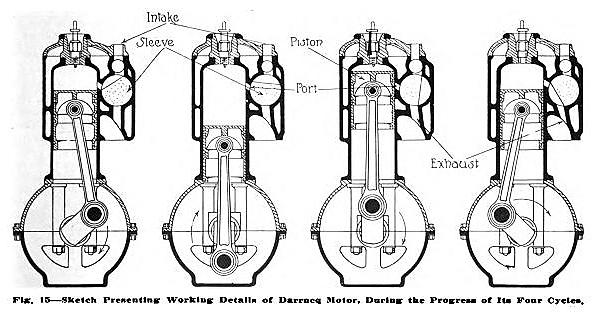

Left: The Darracq rotary valve: 1912

The operation of the valve over a complete cycle.

From The Automobile Journal Volume 33, Number 6, 25 April 1912; p18,19.

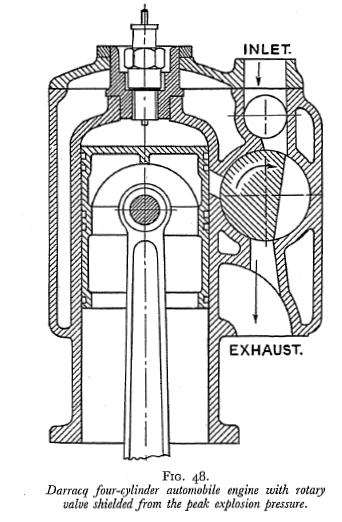

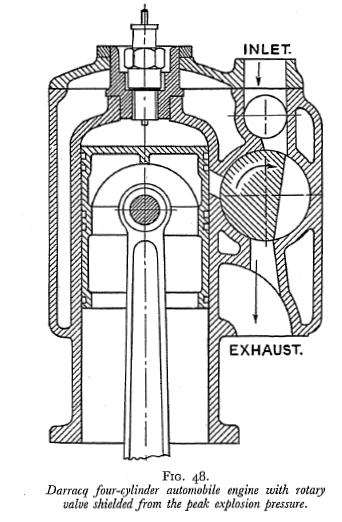

Left: The Darracq rotary valve: 1912

Despite its appalling record, the Henriod valve did have features that made it at least plausible.

Unusually, the valve port opened into the side of the bore, so that the valve was cut off from the combustion chamber when the piston was at the top of its stroke. This was supposed to protect the valve from high pressures and temperatures.

Hunter points out two problems: firstly, on changing from exhaust to induction the cut-out section of the valve carries round a quantity of exhaust gas that dilutes the fresh charge, and secondly, on every rotation the this section carries a portion of fresh charge straight round to the exhaust pipe, causing a dead loss. He also points out that because of the position of the valve port below the piston for one-seventh of the stroke, gases would be trapped above the piston. leading to poor volumetric efficiency.

He also criticises "...the omission of a well-thought-out scheme of lubrication..." which certainly sounds like a major error in this difficult field.

Source: Rotary Valve Engines by Marcus Hunter, Hutchinsons 1946

Left: Darracq rotary valve: 1912

This is believed to be a picture of a Darracq SS of 1912 manufacture.

Charles-Edouard Henriod (the younger brother of Fritz Henriod, who in 1886 made an experimental steam car, and a petrol car in 1893) was Swiss. In 1898 he began making motorcars in Paris. These had a horizontally-opposed air-cooled engine at the front, a three-speed gear system of bevel-gears and pinions, and final drive by side-chains. Over the years Henriod cars became more orthodox, but Charles-Eduoard could not resist the lure of the unconventional. When he stopped making motorcars he designed his rotary-valve system and patented it.

Another licencee of the Henriod patent was Fernand Charron who used it in his Alda cars. It was no more successful than it had been for Darracq. As the French seem wont to say when something is a complete disaster: "It did not give satisfaction."

THE MEAD ROTARY VALVE: 1912

According to the Boston Evening Transcript of 8th March 1913, the rotary valve was the result of seven years of experimetal work by Cyrus W Mead, and represented nearly a quarter of a million dollars in expenditure.

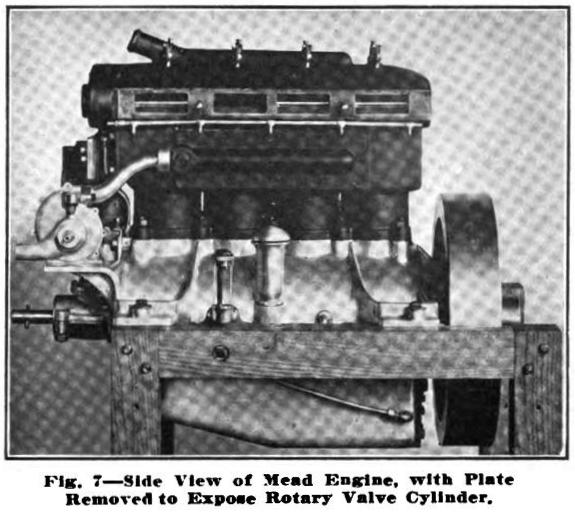

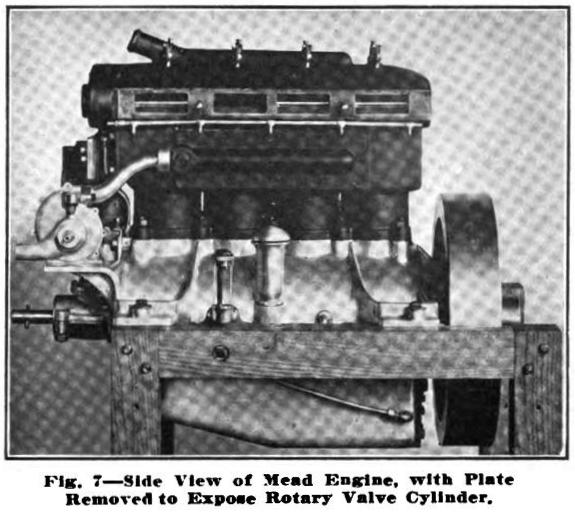

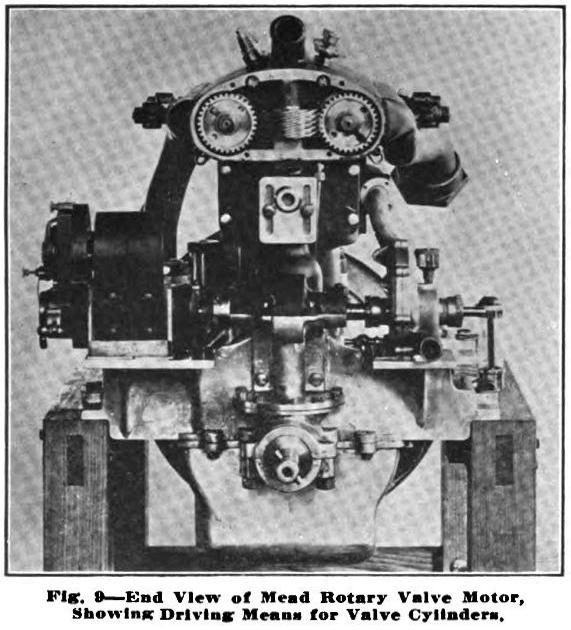

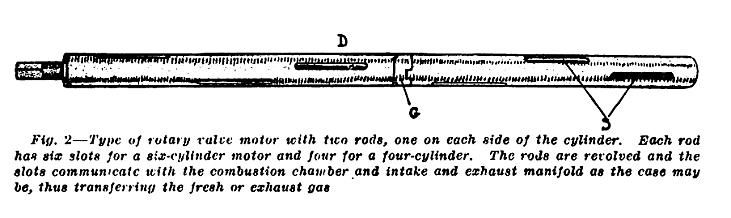

Left: Mead rotary valve engine: 1912

The Mead valve system used two small-diameter valves running longitudinally along each side of the cylinder block. Here one valve can be seen with its cover plate removed. Note once again the fat weighty flywheel.

The Boston Evening Transcript stated that the valve was provided with "liberal cooling". It also said that Mr Mead had made many experiments on lubrication and finally adopted the method of adding 5% of lubricating oil to the fuel; this was presumably in addition to normal sump-based lubrication, and does not inspire confidence, in me at least. I am not sure how it would get oil to the exhaust valve, which no doubt needed it most. At any rate, it must have been a nuisance for the owners.

Apologies for the moire.

US patent 1,007,040

Source: The article "Non Poppet Valve Motor Design" in The Automobile Journal 10 April 1912, volume 33, Number 5, p17,18

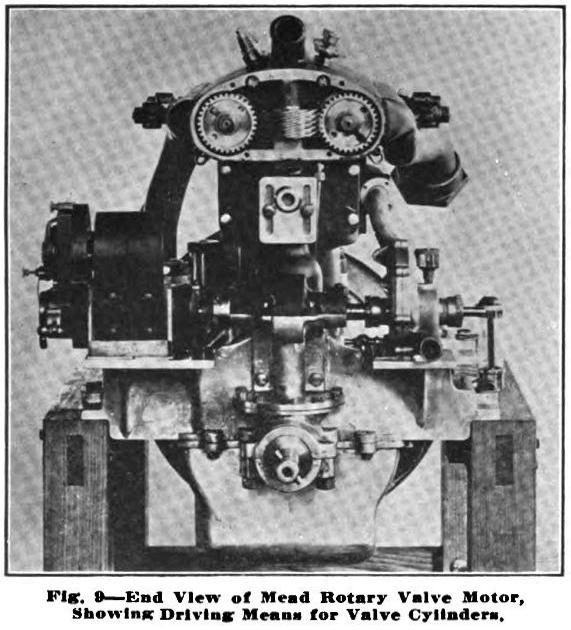

Left: Mead rotary valve engine: 1912

The drive to the two valves, via a vertical shaft and skew gears. The ignition magneto is to the left and the cooling-water pump on the right; both are apparently also driven from the vertical shaft.

The Boston Evening Transcript also claimed that: "In the past few years a great many of these motors have been built and put into operation. They have been subjected to the most severe tests possible... The motors have benn run in cars several hundred thousand miles, and they have been run on dynamometers for long periods of time, and many of the tests were at high speed and high horsepower without stop for several days."

Now if all that was really true, the Mead valve would appear to have been thoroughly reliable and a great success. But I am skeptical, I fear.

US patent 1,007,040

Source: The article "Non Poppet Valve Motor Design" in The Automobile Journal 10 April 1912, volume 33, Number 5, p17,18. Apologies for the moire.

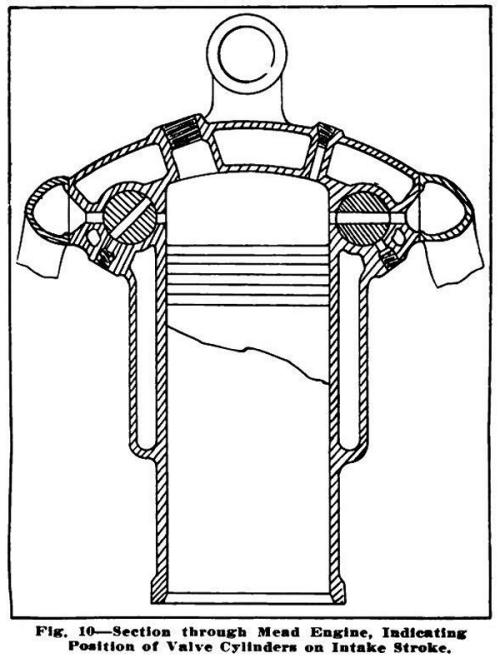

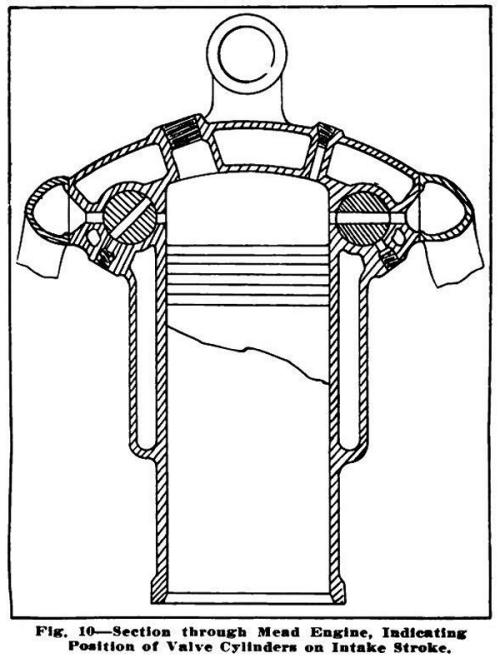

Left: Mead rotary valve engine: 1912

Note the very narrow passages through the valves for both induction and exhaust. Does not look promising for good breathing.

There appear to threaded holes for fitting oil-pipes underneath each valve, which is curious in view of the oil-in-fuel lubrication scheme mentioned above.

The round thing on top is not a lifting eye, but a representation of the cooling water connection.

US patent 1,007,040

Source: The article "Non Poppet Valve Motor Design" in The Automobile Journal 10 April 1912, volume 33, Number 5, p17,18

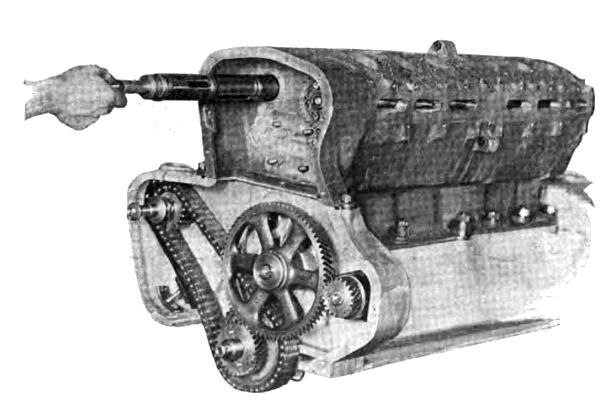

THE SPEEDWELL ROTARY SIX: 1915

According to Motor Age, by the end of 1914 the Speedwell was the only car on the American market with a rotary valve engine, and they were planning to keep it for the 1915 season. This sounds as though it must have been working reasonably well, though it might also have meant that the company was on the brink of bankruptcy and had no money to re-tool a bad design.

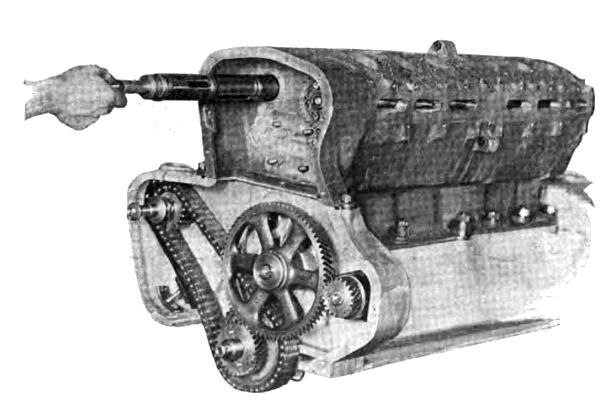

Left: Speedwell in-line six engine: 1915

The disembodied hand is inserting one of the longitudinal valves into the cylinder block. The gearing on display is said to be the timing drive, but it is not clear how it turns the two valve shafts at the top of the block.

The Speedwell engine used a mixture of pump-pressure lubrication for the rotary valves, with splash lubrication of the cylinders. According to Motor Age the valves were grooved longitudinally to distribute lubrication, and this was the vital advance over earlier rotary valve schemes.

Source: Motor Age, 19 Nov 1914, p16-18

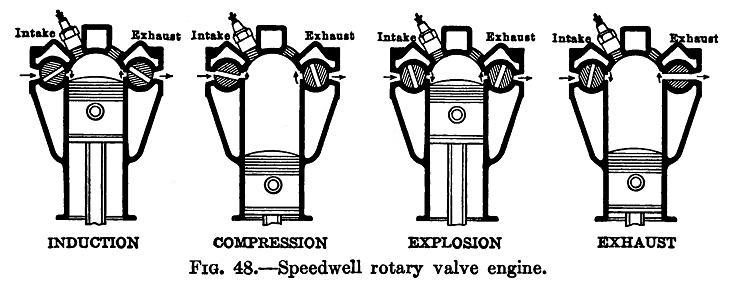

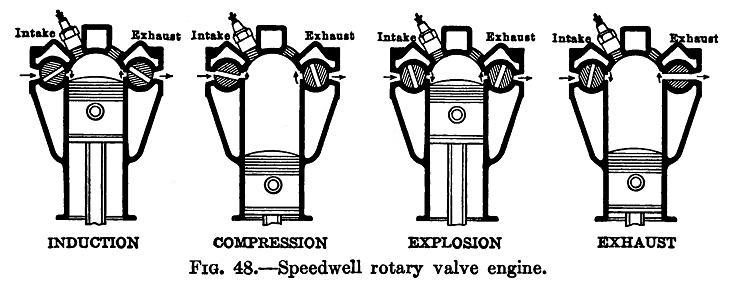

Left: Operation of Speedwell valve

The Speedwell engine used the Mead patents. (see above for Mead)

Source: The Gasoline Automobile by George Hobbs and Ben Elliott, published McGraw-Hill 1915. p34,35

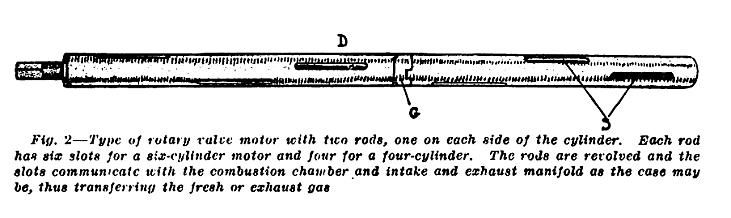

Left: A Speedwell valve shaft

There appears to be some sort of joint in the middle.

Source: Motor Age 17 Dec 1914. p34,35

The Speedwell Motor Car Company was based in Dayton, Ohio. It appears to have succumbed to the Great Dayton Flood rather than troubles with its rotary valves.

THE MUELLER & SCHULER ROTARY VALVE PATENT: 1914

Left: Mueller & Schuler rotary valve patent: 1914

The Mueller patent is the first appearance of a Geneva or Maltese-cross start-stop drive to the valves, though the basic principle was anticipated by Vallillee with his rather implausible ratchet drive, shown above. The Maltese-cross scheme reappeared several times at later dates, for example in the Mellors rotary valve system.

This shows a plan of the cylinder head, with the drive arrangements for the valves of two adjacent cylinders.

US Patent 1,098,679

Left: Mueller & Schuler rotary valve patent: 1914

The horizontal shaft drove two Maltese-cross mechanisms via bevel gears to index the valves of two of the cylinders in a four-cylinder engine.

The text of the patent makes no reference at all to lubrication. Bearing in mind the problems that other workers in the field had with this, it suggests that Mueller & Schuler had not got very far with practical engine development.

Paul Mueller and Ludwig Schuler lived in Brooklyn, New York. Their patent was assigned to the L-M-S Motor Company of Esopus, New York.

US Patent 1,098,679

THE MINERVA ROTARY VALVE SYSTEM: 1925

This rotary valve was used by the Minerva Company, who made luxury motorcars in Belgium. There is some more information on the company here; (external link) it says they made Knight double-sleeve valve engines under licence, but strangely fails to mention rotary valves at all. The valve was invented by M. Bournonville, a Belgian engineer; after two years of development work Minerva believed they had an engine that could challenge the Knight sleeve-valve type, and which was of greater reliability than they had seen before. The Minerva-Bournonville rotary valve is mentioned in "Modern Aviation Engines" By Major Victor Page (Norman Henley Publishing Company) in 1929, so it was still live issue at that date.

Left: The Minerva-Bournonville rotary valve

According to Newton & Steeds:

"It has shown under severe test conditions remarkable reliability and freedom from any tendency to seize up or give trouble through scoring."

From The Motor Vehicle by Newton & Steeds, pub Iliffe, date unknown but certainly post-1921, p71

Reference: Automobile Engineering Vol XVII No228 1927-5

The rotating valve-block V ran horizontally across the top of the engine, and had ports R which allowed the inlet manifold I and the exhaust manifold E to communicate with the cylinder at the right time. Each valve-block V was pressed against its seating by two segmental saddles, on the top which bore a wedge W through two steel balls to ensure uniform distribution of the pressure; the spring-loading on W could be adjusted by screw and lock-nut S.

Left: The Minerva-Bournonville engine

This is believed to be a drawing of a Minerva-Bournonville rotary valve engine. Confusingly it appears to have seven cylinders, but what looks like a connecting rod in the centre of the crankshaft is actually a structure supporting a central crankshaft bearing. Minerva made fours, sixes, and straight-eight engines.

The Japan Society of Mechanical Engineers

For a six-cylinder engine two valve blocks were provided, each serving three cylinders. Because of the multiple ports spaced at 120 degrees, the valves only had to rotate at one-sixth engine speed, which must have reduced problems with wear. Drive was by a double roller chain from a gear-driven countershaft running at one third engine speed.

Left: The Minerva-Bournonville valve

This shows the valve partially withdrawn from the cylinder block. The two saddles can be seen on top of the block.

The Japan Society of Mechanical Engineers

The Minerva company suffered in the financial crisis of the early 1930s. It was restructured as Soci�t� Nouvelle Minerva but in 1934 merged with the other major Belgian car-maker Imperia.

THE CROSS ROTARY VALVE SYSTEM: 1920-1940

Roland Cross was undoubtedly the great British exponent of the horizontal rotary valve, and he appears to have got nearer to making it work properly than anyone else. Cross began his work on rotary valve engines in 1920. The project lapsed in 1945, squeezed out by the demand for components from his company for conventional aero-engines. He died in 1970.

Left: Roland C Cross looking quietly confident

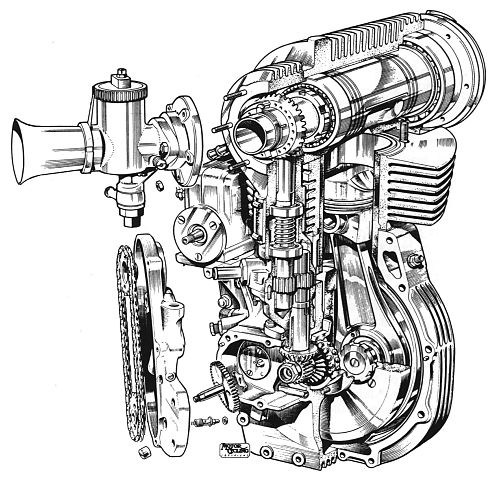

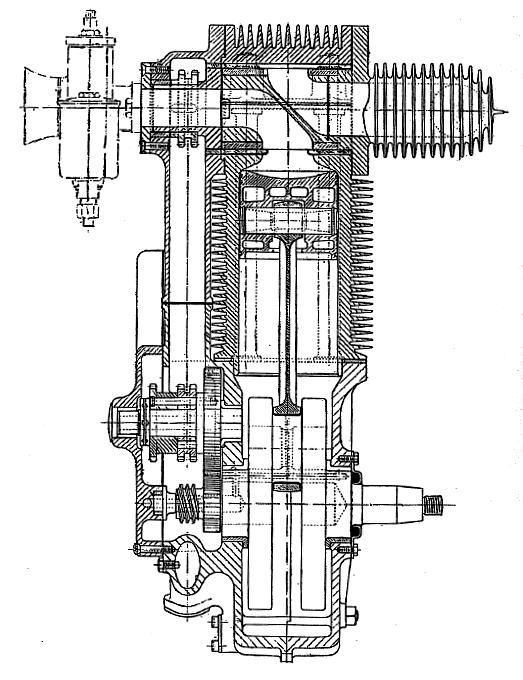

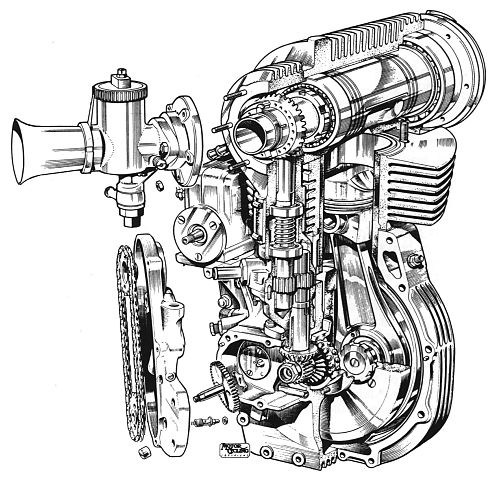

Left: Cross section of an early Cross rotary valve engine

This shows the basic principle of the Cross rotary valve. It is believed to be a drawing of the "Cross engine with split rotary valve housing" shown below, this judgement being based on the enclosed chain drive and the shape of the finned exhaust manifold.

The induction path goes through the centre of the valve drive sprocket at top left, while the exhaust goes out at top right. Note the very short inlet and exhaust paths, which were supposed to give the high specific output claimed for this engine. Another interesting point is that the 2:1 reduction required for the valve drive is achieved by a pair of gears driven from the crankshaft, and the chain drive is 1:1. The earlier engine with the "solid valve housing" shown below has a chain drive with a 2:1 ratio, eliminating the gears. Why this simpler arrangement was departed from is not currently clear, but it might have been done so that the engine height was not unduly increased, allowing it to fit into an existing motorcycle frame for testing.

The small gear to the left of the lower chain sprocket appears to be the magneto drive. The worm gear on the left end of the crankshaft presumably drove an oil pump- forced lubrication of the valve was very important.

According to Hunter the valve was made of aluminium, with a nitralloy steel shell.

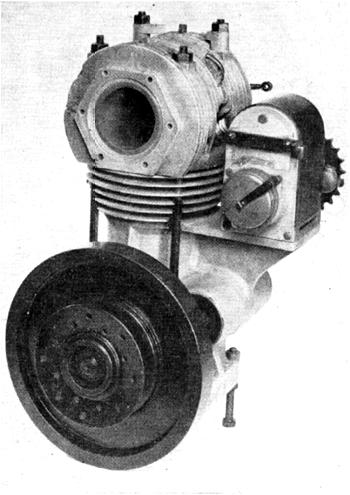

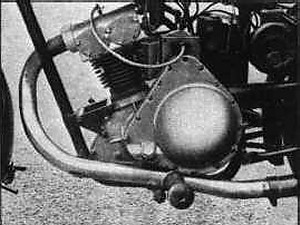

Left: The first Cross rotary valve engine: 1922

Remarkably, this prototype was not an adaption of an existing poppet-valve engine but was designed from scratch. According to Cross, "It gave plenty of power at high speed but very little at low speed, because of leakage, and it was difficult to start because of the over-large valve and the gas leakage."

The second Cross engine was an adaption of of an overhead-camshaft 500cc Sunbeam motor-cycle engine. Cross says "The rotary valve assembly had a sealing device consisting of piston rings on each end of the valve, and a vane on either side of the port running coaxially with the valve.... The machine would start easily and perform well, being a flexible road machine, yet would lap Brooklands track at a speed of over 80 mph, which was good for those days. The sealing device was not fully effective until the machine had done a few hundred miles and some carbon had filled in the gaps left by the machining".

The oil consumption of these early engines was excessive, but Roland Cross was on the case...

From "Address by the Chairman of the Automobile Division: Experiments with Internal-Combustion Engines" by Roland C Cross, delivered at a General Meeting of the Institute of Mechanical Engineers, 8th Oct 1957

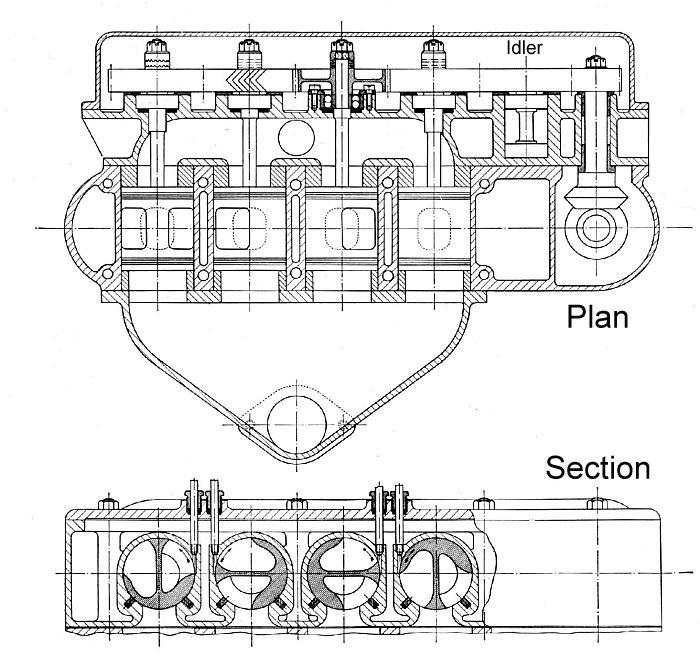

Left: Rotary valves applied to a Rhodes car engine: circa 1925

Around 1925 Roland Cross adapted a 1100cc water-cooled Rhodes car engine to use horizontal rotary valves. He says: "That machine also performed well, was exceedingly smooth an d quiet, and would achieve a speed of about 70 mph on any good road".

The rotary valves were connected to each other via herring-bone spur gears, and were driven by a vertical shaft which presumably interfaced at its lower end with the crankshaft by means of bevel gears. At the top of this vertical shaft more bevel gears drove a short horizontal shaft which drove an idler gear (labelled on the drawing) of twice the size, to reduce the valve speed by 1:2 as required.

From "Address by the Chairman of the Automobile Division: Experiments with Internal-Combustion Engines" by Roland C Cross, delivered at a General Meeting of the Institute of Mechanical Engineers, 8th Oct 1957

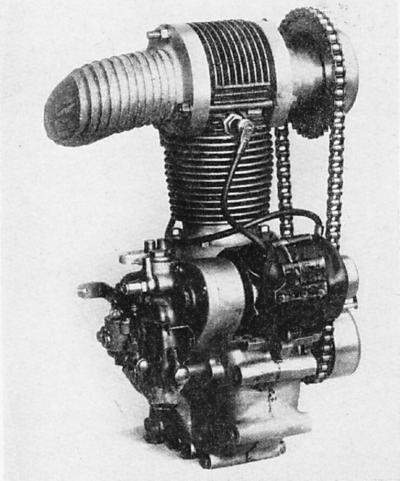

Left: Cross engine with solid rotary valve housing: circa 1930?

Cross developed his rotary valve by bushing the inside of the valve housing with phosphor-bronze and forming the cylinder port in this bush, The edges of the port were sprung towards the valve and gave a better and simpler seal that could accomodate thermal expansion and contraction of the valve. This construction was the basis of experiment until 1935, when the controlled valve loading scheme was evolved.

At the same time he developed a recirculating lubrication system for the valve, which reduced the previously excessive oil consumption until it was competitive with a conventional poppet-valve engine. This oil system was used on all subsequent engines.

From "Address by the Chairman of the Automobile Division: Experiments with Internal-Combustion Engines" by Roland C Cross, delivered at a General Meeting of the Institute of Mechanical Engineers, 8th Oct 1957

Then came the most significant development. Roland Cross: "Towards the end of 1935 I tried the idea of splitting the valve housing along its horizontal centre-line, holding the top half with four long bolts to the crankcase and allowing the cylinder to float vertically. Under the influence of gas pressure in the cylinder, the valve was thus trapped between two halves of the valve housing. The effect of that modification was remarkable. These engines now had wonderful gase sealing, and the slow pulling rivalled that of the steam engine. Seizure was eliminated (which seems to indicate that seizure was not unknown with the earlier versions- DS) and the bearing metal for the valve was the same metal as that of the cylinder."

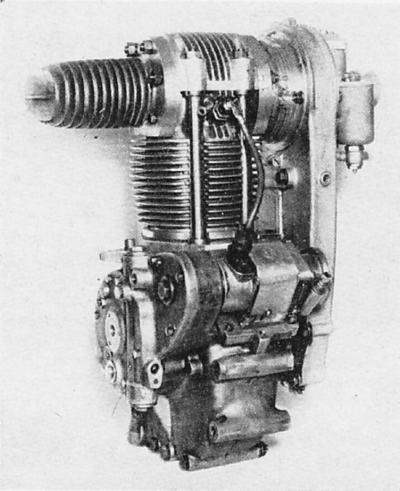

Left: Cross engine with split rotary valve housing: circa 1935

This 500cc single-cylinder engine completed a 10-hour test at 6000 rpm.

Note there are four bolts joining the top of the valve housing and the crankcase. The chain drive to the valve is now decently enclosed; the carburettor can be seen at extreme top right.

From "Address by the Chairman of the Automobile Division: Experiments with Internal-Combustion Engines" by Roland C Cross, delivered at a General Meeting of the Institute of Mechanical Engineers, 8th Oct 1957

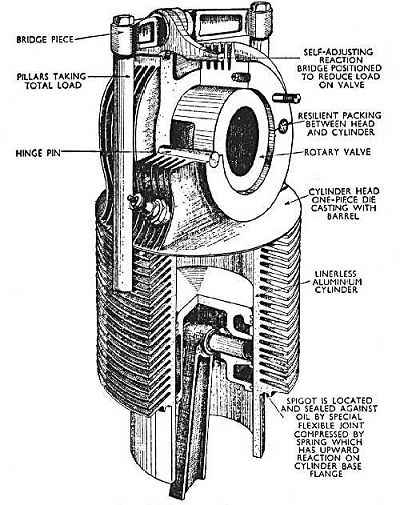

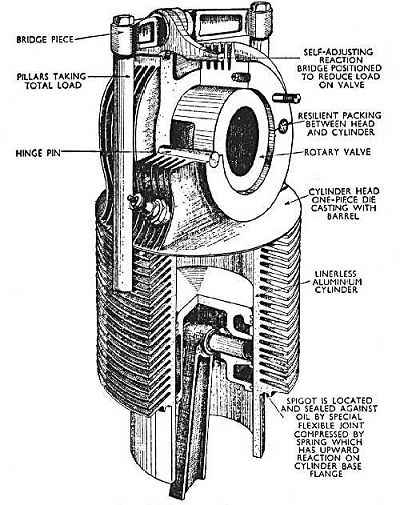

Left: The Cross rotary valve: circa 1935

This is one of the later Cross designs, from around 1935. This version has only two bolts joining the top of the valve housing and the crankcase.

The "reaction bridge" shown in the picture at left absorbs the upward forces on the horizontal valve assembly, and is supposed to have reduced the gas forces on the actual valve. At the moment I'm not quite sure I understand how it worked.

One problem was fouling of the spark plug by oil sprayed from the rotating valve; wiping seals were added to later versions of the engine to control this.

The split valve housing permitted a balanced loading system to control the forces on the valve. Wear was compensated for, lubrication and oil recovery were good, and it is reported that there was no danger of seizure. The sealing problems that other approaches suffered from were solved, and there seems possible that Cross had an effective and practical design which under other circumstances could have reached quantity production; it would probably have been more profitable than the Wankel if it had. On the other hand, Norton had very little success with a similiar concept- see below.

Unlike the Aspin, the Cross valve was always driven at constant speed from the crankshaft.

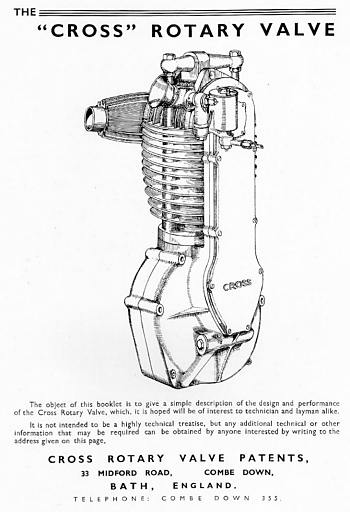

Left: The cover of a booklet the Cross company published to publicise their rotary valve system. Date unknown, but some time after 1935

Note that Combe Down phone numbers only had three digits in those days.

Cross entered two rotary valve motorcycles in the 1935 TT races on the Isle of Man, but one machine proved too slow to qualify, while the other withdrew after two laps with "sparkplug trouble" which may well refer to the problems with plug oiling mentioned above.

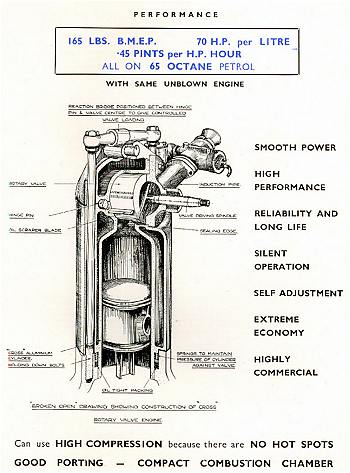

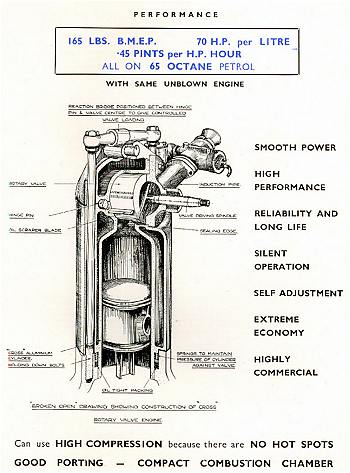

Left: One of the inner pages of the booklet the Cross company published.

The performance and fuel consumption figures claimed here were remarkably good for their day. Whether the engines were ever subjected to impartial testing is not currently known.

At least one Cross rotary-valve motorcycle is known to exist in running order; it is brought to a vintage vehicle rally each year by an ex-Cross employee.

Above: A contemporary display of Cross prototype engines and components at the Sammy Miller Museum in Hampshire

Photograph by Chris Pitt. Used with permission.

Cross evolved a process for the manufacture of high performance piston rings from wire for his rotary valve engine. I am glad to report that the company he founded to make these still exists. See the Cross Manufacturing Company, and look at "history" under the Overview tab. The Cross family continues to be deeply involved, with the third generation continuing the engineering tradition started by their grandfather, working alongside Rodney Cross, surviving son of the founder.

THE ASPIN ROTARY VALVE SYSTEM: 1933-1977

This rotary valve concept by Frank Aspin has a conical vertical valve rotating above the cylinder. The Aspin is probably the best-known rotary valve after the Cross, but it seems to have suffered significantly more technical difficulties.

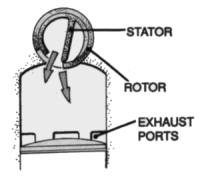

Left: One version of the Aspin rotary valve. Note the conical thrust bearing C, intended to absorb the upward thrust of high pressures in the cylinder. This version has no rotor cooling.

Aspin's first experimental engine was a 250cc machine, based on a Rudge 250cc motorcycle engine. It was built in 1933. Aspin claimed that it produced 18 bhp at 7500 rpm, 31 bhp at 10,000 rpm, and was capable of a maximum speed of 14,000 rpm. It used a 14:1 compression ratio, implying great resistance to pre-ignition, given the low-octane petrol of the time, and this was ascribed to the absence of a hot exhaust poppet valve in the cylinder.

All these figures were startlingly high for the engine technology of the time, and it appears that they were greeted with some disbelief. A recurring theme in the Aspin story is impressive claims for performance, without backing from independent testing.

An Aspin modified Velocette 350cc engine was tested without much success by the Velocette factory in Birmingham in 1936.

By 1939 Aspin had decide it was necessary to liquid-cool the valve rotor to prevent distortion. This change did not greatly reduce the heating problems but it did require the spark-plug to be moved away from its central location, and it was placed at the side of the cylinder, placed so the rotating valve uncovered it at the right time for ignition. The valve rotor at this point was made of case-hardened nickel steel, rotating in an aluminium-bronze housing. Performance was once again claimed to be exceptionally good, but lubrication problems persisted, and the engine required careful warming up since heavy-footed use when cold would be certain to cause seizure of the valve rotor.

At some point Aspin tried a variable-speed drive to the rotor, ie changing speed during the combustion cycle but still in sync with the crankshaft; the idea being that the rotor would be moving relatively slowly during the high-friction parts of the cycle. It does not appear to have been a success, and would certainly have added complications to what is (in principle) a beautifully simple design.

In 1944 the magazine Autocar tested a family car with a four-cylinder Aspin engine.

In the 1960's an Aspin-converted 8.6 litre Leyland lorry engine was used to power a bus operated by The Northern Ireland bus company. At this point Aspin was using a lead-beryllium coating on the rotors to reduce friction. The bus ran successfully for an unknown period, recorded only as "many thousands of miles" until oil consumption abruptly climbed as the special coating on the valve rotors wore off. No further testing was done so the results cannot have been too impressive.

Aspin developed his rotary valve concept over more than thirty years, and there is not space here to trace the detailed evolution of his ideas. In essence, Aspin could build an engine with high oil consumption and good reliability, or with normal oil use but having a distressing tendency for the rotary valves to seize up solid. He never resolved this problem, and many others also failed.

Aspin's last rotary valve patent was taken out in 1977 (US 4033317) and I believe he died shortly afterwards.

There is a very fine site on the Aspin valve and its engines here.

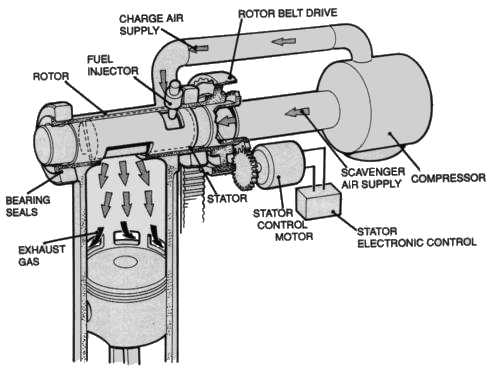

THE FROEDE ROTARY VALVE: 1950s.

Walter Froede was the head of the German company NSU's motorcycle racing program; at the time, NSU was the largest builder of motorcycles in the world.

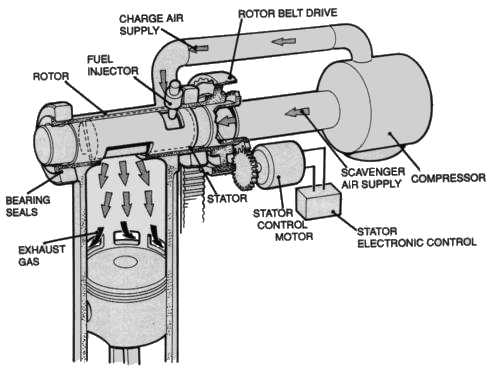

Left: Froede rotary valve in a 125cc racing motorcycle engine. Valve rotor coloured pink.

The engine is tilted over to the left, and the piston is shown at TDC. The rotary valve was driven at a constant 1/4 of crankshaft speed. Although initially successful in racing, it was not repeated, probably due to the demise of NSU.

Later NSU introduced the famous Wankel rotary IC engine, but its poor reliability and short service life finished off the company and NSU was absorbed by Audi.

FELIX WANKEL AND ROTARY VALVES: 1935-1950s.

Felix Wankel, the originator of the famous rotary engine, was involved from 1930 to 1945 in the development of a rotary disc valves for use in aircraft and torpedo engines. His primary expertise was in the difficult business of sealing. During this time he worked at BMW, DVL, Daimler-Benz, Lilienthal and Junker Aircraft.

Various sources state that he was involved in developing the "Daimler-Benz DB601 V-12 rotary disk valve aircraft engine" but other sources say that this engine had four conventional poppet valves. This mystery currently remains unresolved. He certainly worked on the Junkers Jumo KM8 torpedo engine, which had to fit into a cylindrical casing that had no room for conventional valvegear. The short working life of a torpedo engine meant that rapid wear of the rotary valve disc was not an issue.

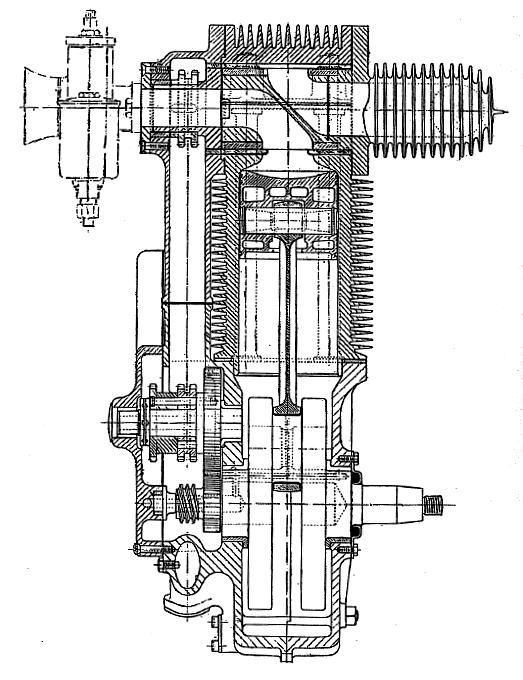

Left: Cross-section of a Junkers Jumo KM8 disc-valve engine, enclosed in its torpedo casing.

The disc valve is visible on the right side of the engine, just above the piston.

The engine had eight liquid-cooled cylinders of 90mm bore by 85mm, stroke arranged as a V-8 with a 90deg angle. The total swept volume was 4.34 litres and the compression ratio was 6.6 to 1. Output was 275 HP at 3650 rpm. It ran on a mixture of petrol, oxygen, and its own exhaust gas- the latter presumably to dilute the oxygen to a manageable content.

A production order for 100 engines was issued towards the end of WW2 but was never completed. A prototype was examined by British and American intelligence engineers, who concluded it was "a progressive trend in automotive development." It would appear they were wrong.

Above: Longitudinal section through one cylinder bank of a Junkers Jumo KM8 disc-valve engine.

The disc valves are fitted between upper and lower cylinder heads. They had teeth on their periphery, and formed two gear trains without the need for idlers or extra gearwheels. The train of valve discs was driven by bevel gears from the crankshaft, with splined connections to allow valve timing to be altered.

In 1951 NSU became interested in Wankel's rotary engine project, and he joined them. It seems very likely he was involved in the design of the Froede rotary valve shown above.

THE MELLORS ROTARY VALVE SYSTEM: 1940s.

Left: The Mellors maltese-cross valve drive system.

The Mellors rotary valve system had two conical valves, one for inlet and one for exhaust. They moved not continuously but in 90-degree steps, driven by a maltese-cross mechanism. When stationary the valves were pressed against their housing by helical springs and so were cooled. Just before each movement they were lifted a few thou from their seatings by a face cam. The valve was thus able to turn freely, and then was released back to its rest position when it stopped.

The use of the maltese-cross or Geneva mechanism was first suggested by Mueller in a 1914 rotary valve patent.

It appears that the valve drive shaft at the bottom of this picture rotates once per cycle, ie at half crankshaft speed. The maltese cross mechanism would have been subjected to some severe accelerations, and I am not too sure how well this would have worked at high rpm.

Left: The Mellors valves in cross-section.

Note the hinged sections and the two little levers at the top. This may have been a method of applying sealing forces to the valves, but I suspect it might have been a misinterpretation of the two levers that lifted the valves when they were due to turn.

Ted Ambrose Mellors was an international motor cycle racer; he became European Champion in 1938. He designed and patented his rotary valve system in the early 1940's, during WW2. See Patent 559830, March 1944.

He died in 1946: see Ted Mellors Biographical Notes (External site)

Left: The Mellors rotary valve system fitted to a 250cc New Imperial engine.

The two bolted-down covers on the side of the cylinder head show the valve locations.

Left: Mellors' prototype rotary valve engine today.

A close-up of the maltese-cross mechanism. The two maltese crosses marked A are driven by pins on opposite sides of the central disc B.

Image kindly provided by John Wood.

THE ALPHA ROTARY VALVE ENGINE: 1962.

In the early Sixties, Alpha Bearings of Dudley in the West Midlands produced an engine in which the flywheel acted as a rotary valve. All I know about it comes from the very informative website here so I will send you straight there.

It is heartening to report that Alpha Bearings are still very much in business.

THE NORTON ROTARY VALVE ENGINE: 1960s

Joe Craig, Norton development engineer, spent two and a half years working on a horizontal rotary valve proposed by Laurie Bond. (The originator of the Bond three-wheeler) The valve design closely followed Cross technology.

There were the usual problems with lubrication,sealing, and plug fouling, and the resulting engine was less powerful than the standard version. Definitely not a success.

Left: The Norton Rotary cylinder head fitted to a Manx Norton motorcycle engine.

The cylindrical valve at the top is driven by bevel gears from a vertical shaft, which is driven from another vertical shaft via two small pinions. The second vertical shaft is driven by bevel gears from the crankshaft. Why there are two vertical shafts is currently unknown to me; it may have been a question of allowing for thermal expansion, or it may just have been a matter of alignment, allowing the bottom end of an existing engine to be used.

Image kindly provided by John Wood.

Left: The Norton Rotary cylinder head seen from the underneath.

The bearing for the vertical drive shaft can be seen at top right.

Image kindly provided by John Wood.

THE ESSO-CROSS ROTARY VALVE ENGINE: 1975

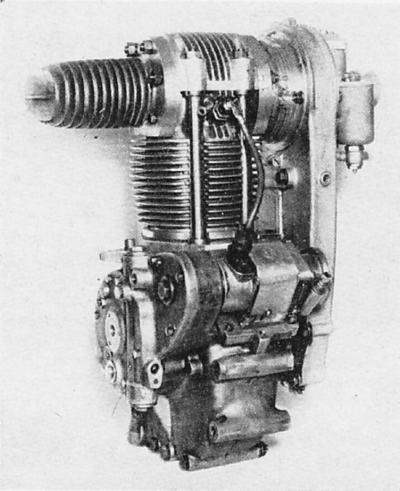

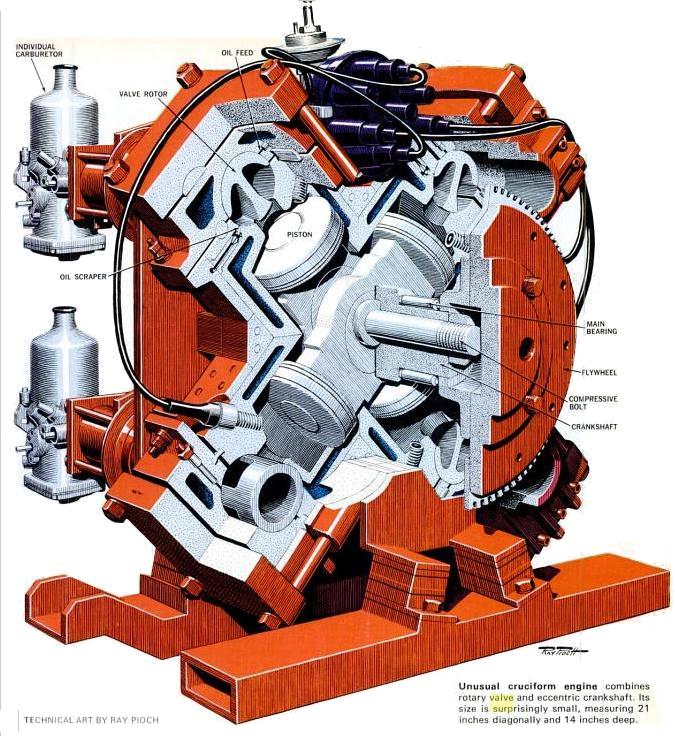

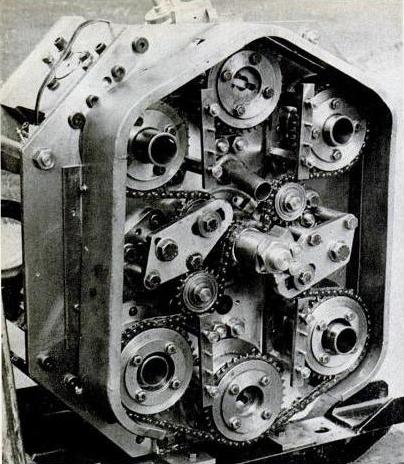

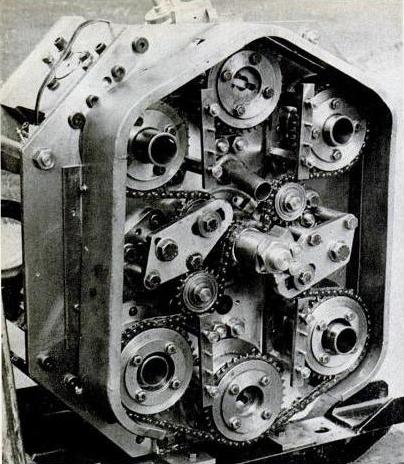

Left: The Esso-Cross rotary valve engine from the exhaust side

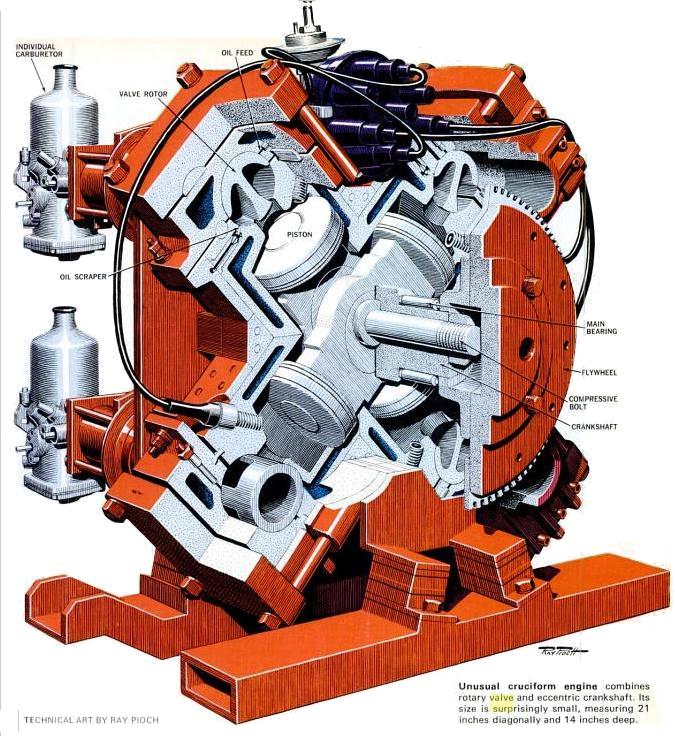

The Esso-Cross rotary valve engine was a joint project between Esso and the Cross Manufacturing Company of Bath. This was after the death of Roland Cross in 1970. Its two radical feature were the rotary valves and an eccentric crank system much the same as that patented by Charles Parsons (of turbine fame) for his epicyclic steam engine in 1877.

The stated engine capacity was 1606 cc (98 cu in) from which it was hope to ultimately get 145 HP. The compression ratio was a high 10.5:1, designed to exploit the absence of exhaust-valve hotspots given by the Cross rotary valves.

The same reaction-bridge arrangement invented by Roland Cross around 1935 was used to control the loading on the rotary valves.

Popular Science July 1975

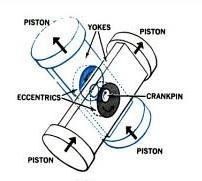

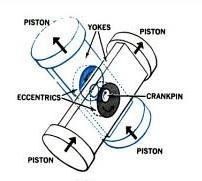

Left: The Esso-Cross eccentric crank system for the rotary valve engine

This arrangement eliminates the connecting rods of a conventional engine. It was also supposed to reduce the number of heavily-loaded bearings from 13 to 5, and eliminate side-forces on the pistons.

rotary valves, but this is not their main unusual feature.

See them on their respective pages:

INTRODUCTION

For almost all its history, the preferred valve for the Internal Combustion engine has been the poppet type. (the etymology of the word "poppet" is an interesting study in itself, but a bit off-topic) There are good reasons for this; see the Appendix on the advantages of the poppet valve.

However, many inventors have been attracted by the apparent simplicity and the uniform motion of rotary valves of one kind or another. There is also the tempting prospect of being able to run on inferior fuels because there was no hot exhaust valve always present in the cylinder to trigger pre-ignition. However, as with both steam and IC rotary engines, the simplicity was more apparent than real, and the engineering problems were daunting.

The basic problem, is that the pressures in the cylinder of an internal combustion engine are high, due to both the compression stroke and the explosion of the fuel-air mixture. This produces large forces on the valve system, however it is contrived; the beauty of the poppet valve is that such forces simply push it harder against its seat, and have no effect at all on the valve-actuating mechanism.

However, the geometry of rotary valve systems is inherently different; in the Aspin concept below, the vertical valve cone is pushed up axially against the cylinder head, while the horizontal Cross valve is pressed up against the top half of the bearing surfaces. In both cases this can cause excessive friction and seizure, the root of the problem being that enormous forces are acting on the valve while it is moving.

There were a large number of rotary valve schemes tried, many of which are only known as patents, the practical success or otherwise being lost to history. The first US patents tracked down so far are by Frayer & Howard in 1907 and 1908. Another early patent was in 1911 by Vallillee (Patent 983328) who used a rotating disc. Several other versions by other people were patented later; see the patent list below. In Britain the two systems which gained the most attention were the Aspin vertical rotating valve and the Cross horizontal rotating valve.

Rotary valves were also tried in steam engines, without conspicuous success. See The Paget Locomotive and the Carel engine on the High-Speed Steam Engines page.

THE CROSSLEY ROTARY VALVE GAS ENGINE: 1886 - 1902

Left: Crossley gas engine with rotary valve.

This is the earliest use of a rotary valve in an internal combustion engine so far discovered. The valve assembly is at the bottom left of the picture, with an adjusting screw sticking out of it. It is driven from the crankshaft by a vertical shaft on the left side of the engine.

Messrs Crossley Bros Ltd (they knew how to name companies in those days) of Openshaw, Manchester, used rotary valves on both vertical and horizontal gas engines running on the Otto cycle. Tube ignition was fitted. Crossley were a successful and respected company, and carried on using these valves from 1886 to 1902; a period of sixteen years that ought to indicate that they worked reasonably effectively and reliably. This is interesting, bearing in mind the problems that later workers struggled with.

The answer is probably that these engines had a very low specific output compared with later designs, and the working pressures were correspondingly low. Also, as a stationary engine, it could be given as much care and adjustment as it needed. In those days it was considered quite normal to give an engine an amount of attention which would be out of the question for, say, a car engine. It was still thought a much better option than a steam engine, where boiler pressure and water level required constant skilled supervision if catastrophe was to be avoided.

Source: Rotary Valve Engines by Marcus Hunter, Hutchinsons 1946

The tireless researchers of The Museum have obtained this unique personal account of a Crossley rotary valve engine in use in 1903:

"Although the engine was several years old, it would toil away hour after hour with an occasional application of ordinary cylinder oil to the rotor, oil probably of an inferior grade by modern standards. There is no doubt that the rotary feature was in many ways a most reliable device; that is to say, there was never a mechanical failure of any kind. On a few occasions the rotor would show signs of overheating, and in these circumstances all that was necessary to regain normal running was to remove the keep from the rotary member, clean the working surfaces with paraffin, and start up again with a fresh application of clean oil.

The keep is spring loaded and adjustable. The operation of adjusting the spring had to be most carefully carried out. The exact loading needed to be such that at maximum engine load, and when thoroughly warmed up, the valve was just on the point of spitting at each explosion. If the spring load was too light, the oil would be blown out each time the engine fired, and if too heavy, any extra expansion of the rotor due to increase in temperature resulted in so much additional friction that the ill-effects became cumulative and the engine would begin to lose speed. However, in spite of all this, the Crossley product was a practical engineering job, and there are many modern appliances which give far more trouble."

Testimony by Marcus Hunter, in 1946. This account refers to the vertical engine illustrated above; it was used for driving machine tools in a private workshop.

The account above is highly revealing. It shows that the Crossley rotary valve engine required almost constant attention, ongoing and critical adjustment of the valve loading, and periodic dismantling.

Left: Inside the Crossley rotary valve.

In this version the cylinder bore was 4.5 inches, and the valve bore 3 inches. The cross bar and cover allowed an adjustable pressure to be put on the valve by springs, to maintain sealing. The valve and the valve box were made of ordinary cast iron as generally used for engine cylinders, and indeed all sorts of machinery, at that date.

Note the convoluted gas passages. In particular, the exhaust passage turns back and runs right past the cylinder wall, which does not look as if it would help cooling.

Source: Rotary Valve Engines by Marcus Hunter, Hutchinsons 1946

Since 1988 Crossley has been part of the Rolls-Royce Power Engineering group.

THE FRAYER & HOWARD ROTARY VALVE PATENT: 1907

Left: Frayer & Howard rotary valve patent: 1907

This is the earliest internal-combustion rotary valve patent so far unearthed by the untiring staff of The Museum. Note however that Butler was apparently using rotary valves in a compound IC engine in 1904.

The valve is mounted horizontally across the top of the cylinder, like the Cross valve, and driven continuously by chain and sprocket from the crankshaft at half-speed.

Frayer and Howard do seem to have had some idea of what they were up against. The valve, shown in Figs 3 and 4, was designed not to touch the surounding metal, but maintain a 2-thou clearance, the gap being flooded with lubricating oil. The valve rotated in ball bearings at each end, protected from the exhaust gases by two sets of sealing rings. (19,20,21,22) It sounds plausible, but I wonder how much oil would be lost into the induction and exhaust passages.

Nothing is currently known as to how much success Frayer and Howard had with their invention. They are unknown to Google.

US Patent 908,656

THE VALLILLEE ROTARY VALVE PATENT: 1911

Left: The Vallillee rotary valve patent: 1911

The rotary valve has an H cross-section and sits on top of the cylinder. It is rotated intermittently via cam 38 and lever 35, that work a ratchet drive 42 on top of the cylinder, the idea presumably being that the valve would be stationary during the parts of the combustion cycle that had high-pressure in the cylinder and would tend to jam the valve.

This is the first known proposal to use intermittent drive to a rotary valve. It looks rather impractical to me.

Leonard Archibal Vallillee lived in Buckingham, in the province of Quebec. Unlike most of the inventors in these pages, he is known to Google. He was born in 1887, the son of John Edward Vallillee (born circa 1863 in Buckingham, Quebec) and Mary McCormick.

US Patent 983,328

ROTARY VALVES BECOME THE VOGUE

In the period 1911-1912 there was a remarkable flurry of activity in the field of rotary valves. Engines using them were unveiled by Itala, Castiglione-Bolton, and Darracq in Europe, and by Mead, Reynolds and The Silent Valve Company in the USA. Rotary valves had, to some extent, become the fashion. But they still did not work very well.

THE ITALA ROTARY VALVE: 1911

Itala was a car manufacturer based in Turin, Italy from 1904-1935. See Itala in Wikipedia. Water-cooled rotary valves were fitted to models announced at the 1911 Olympia Motor Car Show. At first only a 35 HP model was displayed, but 25 and 50 HP versions were said to be on the way.

Left: The Itala rotary valve : 1911

Two rotary valves were used, each placed vertically and serving the two adjacent cylinders. Each cylinder had only one port, which carried both inlet and exhaust, while the valve, which turned at one-quarter engine speed, had an internal division so that the inlet was drawn in from the bottom and the exhaust passed out through the top.

Cooling water for the valve passed into it at the centre, passed down one side of the valve body and up the other, and left by an annular port at the top. A centrifugal pump assisted water circulation.

The crankshaft carried a helical gear that drove a side shaft; this in turn drove the two vertical valve spindles through 'high-efficiency' worm gears. Each valve spindle incorporated a breaking-piece (presumably some sort of shear-pin) to minimise damage to the engine if one of the valves seized.

A small hole was drilled through the valve body in such a position that it carried the pressure on firing through to the opposite side of the valve, into a recess of the same area as the valve port, to balance the loading.

Despite ingenious design, high standards of construction, and some very favourable reports (eg from Autocar) the Itala valve did not prosper. Hunter says "...it is evident from a careful study of the design that it calls for the highest grade of materials and workmanship; in fact every technical defect which might be possible seems to have been overcome by lavish expenditure and detail embellishment... these opinions are expressed: (1) there are too many parts, and (2) skilled experience is required for maintenance, greater than can generally be commanded..."

This is all a bit vague; perhaps however it boils down to the Itala rotary valve being expensive and unreliable. I suspect those "breaking-pieces" saw a lot of action.

Source: Rotary Valve Engines by Marcus Hunter, Hutchinsons 1946

Rankin Kennedy's "The Book of the Motor Car" published in 1913, had this to say:

"Now for the first time a high-speed multiple cylinder engine without reciprocating parts, is available in a throughly practical form, so well thought out in detail and so beautifully constructed that its possession and use cannot be less satisfactory to the fortunate owner than the contemplation of the design is to the engineering critic." which, quite frankly, is laying it on a bit thick. One can only assume that news of valve troubles had not reached Mr Kennedy before publication.

Left: Operating cycle of the Itala rotary valve: 1912

Starting with induction and ending with the exhaust stroke. Note the Oldham coupling in valve shaft. This incorporated the 'breaking piece'.

From The Book of the Motor Car Rankin Kennedy, published Caxton 1913

From 1924 the Itala company was being run in receivership. It was bought by truck maker Officine Metallurgiche di Tortona in 1929, and a few more cars were produced, ending in 1935. After that, what was left of the Itala company was bought by Fiat.

THE CASTIGLIONE-BOLTON ROTARY VALVE: 1912

This British rotary valve scheme was put foreward by Castiglione and Bolton. The valve was horizontal, running the length of the engine

Left: Castiglione-Bolton rotary valve engine: 1912

The rotary valve was driven by a vertical shaft through bevel-gearing. It had a water-cooling jacket on its outside, accessed at each end by pumped cooling water.

Below: The Castiglione-Bolton rotary valve: 1912

The valve had a complex system of inlet and exhaust porting, which connected to the cylinder via a single port in the top of the roughly hemispherical combustion chamber.

The view at 7 is of a complete valve for two cylinders.

From the The Automobile Journal Volume 33. Number 7 May 10, 1912, page 46

The engine seems to have had little success, as the Castiglione-Bolton team is unknown to Google. It also seems to have escaped the notice of Hunter.

THE DARRACQ-HENRIOD ROTARY VALVE: 1912

The Darracq-Henrold rotary valve engine was a French design, from the well-known car firm of Darracq. According to one source "In 1912 the firm succumbed to the vogue for abolition of the poppet valve with a near disastrous range of rotary valved cars under Henriod patents." which sounds as if things didn't go too well, and also gives a hint as to why so many rotary valves appeared around 1912- it was "the vogue".

In 1912 Darracq produced "syst�me Henriod" engines of 2613 cc and 15 HP (uprated to 2951 cc the next year) and a 3969cc version of 20 HP.They were described as Type SS, or 'sans soupapes', meaning without valves- not strictly true, of course. Hunter says, apparently acidly, "'Sans soupapes' is the term which the French give to every engine which has other than poppet-valves." These engines were also described as "completely gutless", presumably due to breathing difficulties, and were prone to seizure. Both profits and Darracq's reputation plummeted, and the debacle seems to have prompted Alexandre Darracq to retire from car manufacture; he sold his company to British financial interests in 1913. Apparently one 1912 SS car is still in existence, but in need of restoration. According to Hunter (p102) only a few engines actually reached customers, so for the effect on the company to be so drastic, their performance must have been truly awful.

Left: A Darracq four-cylinder engine with rotary valve: 1912

The horizontal valve ran the length of the cylinder block, being driven from the crankshaft at half engine speed by a vertical shaft with skew gears. The ignition magneto can be seen to the left behind the vertical shaft.

Look at the size of that flywheel!

From The Automobile Journal Volume 33, Number 6, 25 April 1912; p18,19. The article spells Henriod as Henrold throughout.

Left: The Darracq rotary valve: 1912

Pretty much self explanatory.

THe flange marked C is for mounting the carburettor. The covers m presumably allowed inspection of the valve.

From The Automobile Journal Volume 33, Number 6, 25 April 1912; p18,19.

Left: The Darracq rotary valve: 1912

The operation of the valve over a complete cycle.

From The Automobile Journal Volume 33, Number 6, 25 April 1912; p18,19.

Left: The Darracq rotary valve: 1912

Despite its appalling record, the Henriod valve did have features that made it at least plausible.

Unusually, the valve port opened into the side of the bore, so that the valve was cut off from the combustion chamber when the piston was at the top of its stroke. This was supposed to protect the valve from high pressures and temperatures.

Hunter points out two problems: firstly, on changing from exhaust to induction the cut-out section of the valve carries round a quantity of exhaust gas that dilutes the fresh charge, and secondly, on every rotation the this section carries a portion of fresh charge straight round to the exhaust pipe, causing a dead loss. He also points out that because of the position of the valve port below the piston for one-seventh of the stroke, gases would be trapped above the piston. leading to poor volumetric efficiency.

He also criticises "...the omission of a well-thought-out scheme of lubrication..." which certainly sounds like a major error in this difficult field.

Source: Rotary Valve Engines by Marcus Hunter, Hutchinsons 1946

Left: Darracq rotary valve: 1912

This is believed to be a picture of a Darracq SS of 1912 manufacture.

Charles-Edouard Henriod (the younger brother of Fritz Henriod, who in 1886 made an experimental steam car, and a petrol car in 1893) was Swiss. In 1898 he began making motorcars in Paris. These had a horizontally-opposed air-cooled engine at the front, a three-speed gear system of bevel-gears and pinions, and final drive by side-chains. Over the years Henriod cars became more orthodox, but Charles-Eduoard could not resist the lure of the unconventional. When he stopped making motorcars he designed his rotary-valve system and patented it.

Another licencee of the Henriod patent was Fernand Charron who used it in his Alda cars. It was no more successful than it had been for Darracq. As the French seem wont to say when something is a complete disaster: "It did not give satisfaction."

THE MEAD ROTARY VALVE: 1912

According to the Boston Evening Transcript of 8th March 1913, the rotary valve was the result of seven years of experimetal work by Cyrus W Mead, and represented nearly a quarter of a million dollars in expenditure.

Left: Mead rotary valve engine: 1912

The Mead valve system used two small-diameter valves running longitudinally along each side of the cylinder block. Here one valve can be seen with its cover plate removed. Note once again the fat weighty flywheel.

The Boston Evening Transcript stated that the valve was provided with "liberal cooling". It also said that Mr Mead had made many experiments on lubrication and finally adopted the method of adding 5% of lubricating oil to the fuel; this was presumably in addition to normal sump-based lubrication, and does not inspire confidence, in me at least. I am not sure how it would get oil to the exhaust valve, which no doubt needed it most. At any rate, it must have been a nuisance for the owners.

Apologies for the moire.

US patent 1,007,040

Source: The article "Non Poppet Valve Motor Design" in The Automobile Journal 10 April 1912, volume 33, Number 5, p17,18

Left: Mead rotary valve engine: 1912

The drive to the two valves, via a vertical shaft and skew gears. The ignition magneto is to the left and the cooling-water pump on the right; both are apparently also driven from the vertical shaft.

The Boston Evening Transcript also claimed that: "In the past few years a great many of these motors have been built and put into operation. They have been subjected to the most severe tests possible... The motors have benn run in cars several hundred thousand miles, and they have been run on dynamometers for long periods of time, and many of the tests were at high speed and high horsepower without stop for several days."

Now if all that was really true, the Mead valve would appear to have been thoroughly reliable and a great success. But I am skeptical, I fear.

US patent 1,007,040

Source: The article "Non Poppet Valve Motor Design" in The Automobile Journal 10 April 1912, volume 33, Number 5, p17,18. Apologies for the moire.

Left: Mead rotary valve engine: 1912

Note the very narrow passages through the valves for both induction and exhaust. Does not look promising for good breathing.

There appear to threaded holes for fitting oil-pipes underneath each valve, which is curious in view of the oil-in-fuel lubrication scheme mentioned above.

The round thing on top is not a lifting eye, but a representation of the cooling water connection.

US patent 1,007,040

Source: The article "Non Poppet Valve Motor Design" in The Automobile Journal 10 April 1912, volume 33, Number 5, p17,18

THE SPEEDWELL ROTARY SIX: 1915

According to Motor Age, by the end of 1914 the Speedwell was the only car on the American market with a rotary valve engine, and they were planning to keep it for the 1915 season. This sounds as though it must have been working reasonably well, though it might also have meant that the company was on the brink of bankruptcy and had no money to re-tool a bad design.

Left: Speedwell in-line six engine: 1915

The disembodied hand is inserting one of the longitudinal valves into the cylinder block. The gearing on display is said to be the timing drive, but it is not clear how it turns the two valve shafts at the top of the block.

The Speedwell engine used a mixture of pump-pressure lubrication for the rotary valves, with splash lubrication of the cylinders. According to Motor Age the valves were grooved longitudinally to distribute lubrication, and this was the vital advance over earlier rotary valve schemes.

Source: Motor Age, 19 Nov 1914, p16-18

Left: Operation of Speedwell valve

The Speedwell engine used the Mead patents. (see above for Mead)

Source: The Gasoline Automobile by George Hobbs and Ben Elliott, published McGraw-Hill 1915. p34,35

Left: A Speedwell valve shaft

There appears to be some sort of joint in the middle.

Source: Motor Age 17 Dec 1914. p34,35

The Speedwell Motor Car Company was based in Dayton, Ohio. It appears to have succumbed to the Great Dayton Flood rather than troubles with its rotary valves.

THE MUELLER & SCHULER ROTARY VALVE PATENT: 1914

Left: Mueller & Schuler rotary valve patent: 1914

The Mueller patent is the first appearance of a Geneva or Maltese-cross start-stop drive to the valves, though the basic principle was anticipated by Vallillee with his rather implausible ratchet drive, shown above. The Maltese-cross scheme reappeared several times at later dates, for example in the Mellors rotary valve system.

This shows a plan of the cylinder head, with the drive arrangements for the valves of two adjacent cylinders.

US Patent 1,098,679

Left: Mueller & Schuler rotary valve patent: 1914

The horizontal shaft drove two Maltese-cross mechanisms via bevel gears to index the valves of two of the cylinders in a four-cylinder engine.

The text of the patent makes no reference at all to lubrication. Bearing in mind the problems that other workers in the field had with this, it suggests that Mueller & Schuler had not got very far with practical engine development.

Paul Mueller and Ludwig Schuler lived in Brooklyn, New York. Their patent was assigned to the L-M-S Motor Company of Esopus, New York.

US Patent 1,098,679

THE MINERVA ROTARY VALVE SYSTEM: 1925

This rotary valve was used by the Minerva Company, who made luxury motorcars in Belgium. There is some more information on the company here; (external link) it says they made Knight double-sleeve valve engines under licence, but strangely fails to mention rotary valves at all. The valve was invented by M. Bournonville, a Belgian engineer; after two years of development work Minerva believed they had an engine that could challenge the Knight sleeve-valve type, and which was of greater reliability than they had seen before. The Minerva-Bournonville rotary valve is mentioned in "Modern Aviation Engines" By Major Victor Page (Norman Henley Publishing Company) in 1929, so it was still live issue at that date.

Left: The Minerva-Bournonville rotary valve

According to Newton & Steeds:

"It has shown under severe test conditions remarkable reliability and freedom from any tendency to seize up or give trouble through scoring."

From The Motor Vehicle by Newton & Steeds, pub Iliffe, date unknown but certainly post-1921, p71

Reference: Automobile Engineering Vol XVII No228 1927-5

The rotating valve-block V ran horizontally across the top of the engine, and had ports R which allowed the inlet manifold I and the exhaust manifold E to communicate with the cylinder at the right time. Each valve-block V was pressed against its seating by two segmental saddles, on the top which bore a wedge W through two steel balls to ensure uniform distribution of the pressure; the spring-loading on W could be adjusted by screw and lock-nut S.

Left: The Minerva-Bournonville engine

This is believed to be a drawing of a Minerva-Bournonville rotary valve engine. Confusingly it appears to have seven cylinders, but what looks like a connecting rod in the centre of the crankshaft is actually a structure supporting a central crankshaft bearing. Minerva made fours, sixes, and straight-eight engines.

The Japan Society of Mechanical Engineers

For a six-cylinder engine two valve blocks were provided, each serving three cylinders. Because of the multiple ports spaced at 120 degrees, the valves only had to rotate at one-sixth engine speed, which must have reduced problems with wear. Drive was by a double roller chain from a gear-driven countershaft running at one third engine speed.

Left: The Minerva-Bournonville valve

This shows the valve partially withdrawn from the cylinder block. The two saddles can be seen on top of the block.

The Japan Society of Mechanical Engineers

The Minerva company suffered in the financial crisis of the early 1930s. It was restructured as Soci�t� Nouvelle Minerva but in 1934 merged with the other major Belgian car-maker Imperia.

THE CROSS ROTARY VALVE SYSTEM: 1920-1940

Roland Cross was undoubtedly the great British exponent of the horizontal rotary valve, and he appears to have got nearer to making it work properly than anyone else. Cross began his work on rotary valve engines in 1920. The project lapsed in 1945, squeezed out by the demand for components from his company for conventional aero-engines. He died in 1970.

Left: Roland C Cross looking quietly confident

Left: Cross section of an early Cross rotary valve engine

This shows the basic principle of the Cross rotary valve. It is believed to be a drawing of the "Cross engine with split rotary valve housing" shown below, this judgement being based on the enclosed chain drive and the shape of the finned exhaust manifold.

The induction path goes through the centre of the valve drive sprocket at top left, while the exhaust goes out at top right. Note the very short inlet and exhaust paths, which were supposed to give the high specific output claimed for this engine. Another interesting point is that the 2:1 reduction required for the valve drive is achieved by a pair of gears driven from the crankshaft, and the chain drive is 1:1. The earlier engine with the "solid valve housing" shown below has a chain drive with a 2:1 ratio, eliminating the gears. Why this simpler arrangement was departed from is not currently clear, but it might have been done so that the engine height was not unduly increased, allowing it to fit into an existing motorcycle frame for testing.

The small gear to the left of the lower chain sprocket appears to be the magneto drive. The worm gear on the left end of the crankshaft presumably drove an oil pump- forced lubrication of the valve was very important.

According to Hunter the valve was made of aluminium, with a nitralloy steel shell.

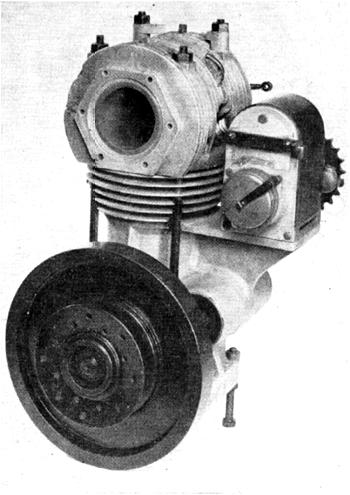

Left: The first Cross rotary valve engine: 1922

Remarkably, this prototype was not an adaption of an existing poppet-valve engine but was designed from scratch. According to Cross, "It gave plenty of power at high speed but very little at low speed, because of leakage, and it was difficult to start because of the over-large valve and the gas leakage."

The second Cross engine was an adaption of of an overhead-camshaft 500cc Sunbeam motor-cycle engine. Cross says "The rotary valve assembly had a sealing device consisting of piston rings on each end of the valve, and a vane on either side of the port running coaxially with the valve.... The machine would start easily and perform well, being a flexible road machine, yet would lap Brooklands track at a speed of over 80 mph, which was good for those days. The sealing device was not fully effective until the machine had done a few hundred miles and some carbon had filled in the gaps left by the machining".

The oil consumption of these early engines was excessive, but Roland Cross was on the case...

From "Address by the Chairman of the Automobile Division: Experiments with Internal-Combustion Engines" by Roland C Cross, delivered at a General Meeting of the Institute of Mechanical Engineers, 8th Oct 1957

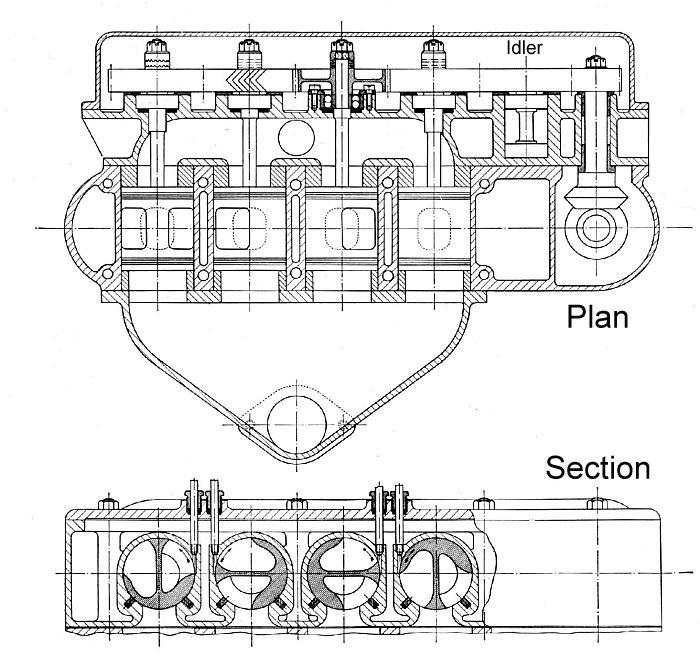

Left: Rotary valves applied to a Rhodes car engine: circa 1925

Around 1925 Roland Cross adapted a 1100cc water-cooled Rhodes car engine to use horizontal rotary valves. He says: "That machine also performed well, was exceedingly smooth an d quiet, and would achieve a speed of about 70 mph on any good road".

The rotary valves were connected to each other via herring-bone spur gears, and were driven by a vertical shaft which presumably interfaced at its lower end with the crankshaft by means of bevel gears. At the top of this vertical shaft more bevel gears drove a short horizontal shaft which drove an idler gear (labelled on the drawing) of twice the size, to reduce the valve speed by 1:2 as required.

From "Address by the Chairman of the Automobile Division: Experiments with Internal-Combustion Engines" by Roland C Cross, delivered at a General Meeting of the Institute of Mechanical Engineers, 8th Oct 1957

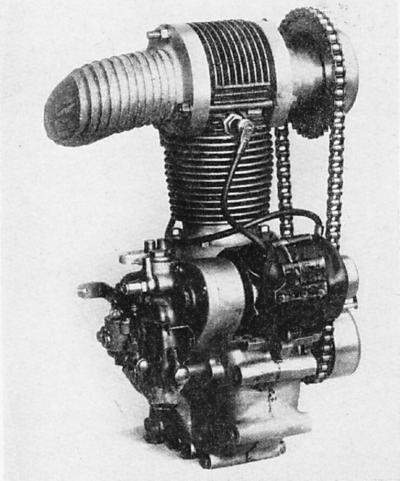

Left: Cross engine with solid rotary valve housing: circa 1930?

Cross developed his rotary valve by bushing the inside of the valve housing with phosphor-bronze and forming the cylinder port in this bush, The edges of the port were sprung towards the valve and gave a better and simpler seal that could accomodate thermal expansion and contraction of the valve. This construction was the basis of experiment until 1935, when the controlled valve loading scheme was evolved.

At the same time he developed a recirculating lubrication system for the valve, which reduced the previously excessive oil consumption until it was competitive with a conventional poppet-valve engine. This oil system was used on all subsequent engines.

From "Address by the Chairman of the Automobile Division: Experiments with Internal-Combustion Engines" by Roland C Cross, delivered at a General Meeting of the Institute of Mechanical Engineers, 8th Oct 1957

Then came the most significant development. Roland Cross: "Towards the end of 1935 I tried the idea of splitting the valve housing along its horizontal centre-line, holding the top half with four long bolts to the crankcase and allowing the cylinder to float vertically. Under the influence of gas pressure in the cylinder, the valve was thus trapped between two halves of the valve housing. The effect of that modification was remarkable. These engines now had wonderful gase sealing, and the slow pulling rivalled that of the steam engine. Seizure was eliminated (which seems to indicate that seizure was not unknown with the earlier versions- DS) and the bearing metal for the valve was the same metal as that of the cylinder."

Left: Cross engine with split rotary valve housing: circa 1935

This 500cc single-cylinder engine completed a 10-hour test at 6000 rpm.

Note there are four bolts joining the top of the valve housing and the crankcase. The chain drive to the valve is now decently enclosed; the carburettor can be seen at extreme top right.

From "Address by the Chairman of the Automobile Division: Experiments with Internal-Combustion Engines" by Roland C Cross, delivered at a General Meeting of the Institute of Mechanical Engineers, 8th Oct 1957

Left: The Cross rotary valve: circa 1935

This is one of the later Cross designs, from around 1935. This version has only two bolts joining the top of the valve housing and the crankcase.

The "reaction bridge" shown in the picture at left absorbs the upward forces on the horizontal valve assembly, and is supposed to have reduced the gas forces on the actual valve. At the moment I'm not quite sure I understand how it worked.

One problem was fouling of the spark plug by oil sprayed from the rotating valve; wiping seals were added to later versions of the engine to control this.